ISSN: 1550-7521

ISSN: 1550-7521

1Leo A. Gher, Associate Professor, Department of Radio-Television

2Kiran Bharthapudi, Doctoral Student, College of Mass Communication & Media Arts, Southern Illinois University Carbondale Carbondale

Visit for more related articles at Global Media Journal

An Attitudinal Study of Five Newly Independent States In the decade leading up to the new millennium, the international community celebrated the end of the Cold War and witnessed the emergence of globalization, a bundle of processes that are cumulative and mutually reinforcing in effect. People now live in an interdependent world where borders no longer define a nation or its security. Today, nation-states remain players on the global stage, but they are now forged by an elaborate socio-political-economic process that includes international institutions, multinational conglomerates, non-governmental organization, and cross border interest groups such as Doctors Without Borders, Green Peace and Amnesty International (Kaldor 2001). Most importantly to this new world order, transnational media have become the harbingers of globalization, and one of the key elements of modernity. As Giddens tells us, “Modernity is inherently globalizing.” (1990). At the end of the 20th Century one region of the world that had been profoundly affected by globalization and transnational media was Eastern Europe. For a very long time the history of Eastern Europe was shaped by its geographic and intellectual position between East and West, and by the hegemonic influences of occidental Europe, Byzantine Russia or the Ottoman Empire. After the collapse of the USSR in 1990, old socialist satellites from the Baltics to the Balkans quickly abandoned the governing ideology of communism and pursued autonomous sovereignty (Mason, 1996). Many of these Eastern European states are now struggling with a difficult transition to democracy. The popular press have labeled such countries “transitioning economies,” but a centralized economy was not the only institution that was forced to confront modernity. Most state institutions were abruptly challenged with the task of reinventing the wheels of government, the workings of their social order, and the effects of globalization. Recent research (Gher 2003) has clearly identified the conflicts that Eastern European transitioning economies are having with modernity. These evolving nations are challenged every day by the strange world of globalization and transnational mass media. The main question of this research centers on the impact of globalization and transnational media in five transitioning states in Eastern Europe: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Croatia and Slovenia. For this research, transnational media is defined as: communication, information or entertainment that crosses international borders without the regulatory constrains normally associated with electronic media. Satellite television is especially important in this process. At the end of 2000, 216 geostationary and more than 150 LEO satellites orbit the Earth, a planetary infrastructure, fully capable of providing direct voice, data, radio and television services to the six billion citizens of the planet (Ricardo 2000). What’s more, American television and film are now the most widely distributed entertainment products in the world. Amin estimates the percentage of American entertainment program penetration at 85 percent globally (1996). For example, in one NIS country examined, on a typical weekday, Croat television (Hrvatski Televizija) aired 221.5 hours of programming via broadcast, cable and satellite; 88.7 percent of that time was filled with foreign programming, mostly American and German. In addition, on the average day, Croatia’s three, public service TV networks broadcast programming for 48 hours; only 25 hours of that schedule (including six hours of proceedings of the parliament) were Croat produced shows. This means that 47.9 percent of Hrvatski Televizija’s three-channel schedule is foreign-produced programming, which is a violation of the European Council’s mandate for membership in the European Union, and a clear example of the impact of transnational media in Eastern Europe. A review of television listings in six regional newspapers found a similar pattern of foreignproduced television programming

In the decade leading up to the new millennium, the international community celebrated the end of the Cold War and witnessed the emergence of globalization, a bundle of processes that are cumulative and mutually reinforcing in effect. People now live in an interdependent world where borders no longer define a nation or its security. Today, nation-states remain players on the global stage, but they are now forged by an elaborate socio-political-economic process that includes international institutions, multinational conglomerates, non-governmental organization, and cross border interest groups such as Doctors Without Borders, Green Peace and Amnesty International (Kaldor 2001). Most importantly to this new world order, transnational media have become the harbingers of globalization, and one of the key elements of modernity. As Giddens tells us, “Modernity is inherently globalizing.” (1990).

At the end of the 20th Century one region of the world that had been profoundly affected by globalization and transnational media was Eastern Europe. For a very long time the history of Eastern Europe was shaped by its geographic and intellectual position between East and West, and by the hegemonic influences of occidental Europe, Byzantine Russia or the Ottoman Empire. After the collapse of the USSR in 1990, old socialist satellites from the Baltics to the Balkans quickly abandoned the governing ideology of communism and pursued autonomous sovereignty (Mason, 1996). Many of these Eastern European states are now struggling with a difficult transition to democracy. The popular press have labeled such countries “transitioning economies,” but a centralized economy was not the only institution that was forced to confront modernity. Most state institutions were abruptly challenged with the task of reinventing the wheels of government, the workings of their social order, and the effects of globalization. Recent research (Gher 2003) has clearly identified the conflicts that Eastern European transitioning economies are having with modernity. These evolving nations are challenged every day by the strange world of globalization and transnational mass media. The main question of this research centers on the impact of globalization and transnational media in five transitioning states in Eastern Europe: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Croatia and Slovenia.

For this research, transnational media is defined as: communication, information or entertainment that crosses international borders without the regulatory constrains normally associated with electronic media. Satellite television is especially important in this process. At the end of 2000, 216 geostationary and more than 150 LEO satellites orbit the Earth, a planetary infrastructure, fully capable of providing direct voice, data, radio and television services to the six billion citizens of the planet (Ricardo 2000). What’s more, American television and film are now the most widely distributed entertainment products in the world. Amin estimates the percentage of American entertainment program penetration at 85 percent globally (1996). For example, in one NIS country examined, on a typical weekday, Croat television (Hrvatski Televizija) aired 221.5 hours of programming via broadcast, cable and satellite; 88.7 percent of that time was filled with foreign programming, mostly American and German. In addition, on the average day, Croatia’s three, public service TV networks broadcast programming for 48 hours; only 25 hours of that schedule (including six hours of proceedings of the parliament) were Croat produced shows. This means that 47.9 percent of Hrvatski Televizija’s three-channel schedule is foreign-produced programming, which is a violation of the European Council’s mandate for membership in the European Union, and a clear example of the impact of transnational media in Eastern Europe. A review of television listings in six regional newspapers found a similar pattern of foreignproduced television programming.

The investigation, at hand, was conducted over a three-year period, starting in the spring of 2000 and ending in the summer of 2002. Two groups of citizens in the Baltic States of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, and in the Balkans States of Croatia and Slovenia were surveyed and interviewed. The Baltic States Survey (Gher 2000), a Likert-style questionnaire, with a coefficient of stability calculated at r = .78, containing four categories (economics, media, law and culture), was used. Initially, this survey contained 32-items and was developed to measure individual perceptions concerning globalization and transnational media. After conducting a pilot study, the scale was reduced to 20 items. Three items measure individual perceptions on economic issues, or people’s opinion about the role that their country plays in the global economy. Five items measure which country’s national interests have a substantial impact on the globalization of media: American, European, Russian or their own country’s interests. Another three items assess the influence of transnational media on local media issues. Additionally, three items consider the influence of transnational media on a nation’s legal issues, while five items measure the consequences of transnational media on a nation’s cultural issues.

Data were collected so that the researcher could compare the responses of random citizens with a special subset of the Eastern European population, a group of educated, media professionals. One Hundred individuals from each group were required. Data from the three-year investigation were combined to create a total sample of 200 surveys from two key regions of Eastern Europe. The countries employed in this research were a sample of convenience for the primary researcher, who was employed as a professor of international media management at Concordia International University in Estonia and the University of Zagreb in Croatia. On-ground research assistants translated and administered the survey instrument. The primary researcher conducted workshops for assistants on testing procedures, language transliteration, back translation, and data recording policies. The data obtained from the surveys were tabulated by the SPSS 11.0 software. Means and standard deviations for each nation were obtained and t-tests were calculated in order to determine the statistical significance of the data. Three research questions were addressed.

1. What are the attitudes of the general population (random citizen) towards globalization and transnational mass media on five Eastern European societies?

2. What are the attitudes of the media personnel (educated, media professionals) towards globalization and transnational mass media on five Eastern European societies?

3. How do the attitudes of educated, media professionals differ from those of average citizens regarding globalization and transnational mass media?

As free and independent nations, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania have existed only briefly twice in the last century: from 1918-1940 and from 1991-2001. At first glance, the similarities among these countries seem more than obvious, but only in recent decades can the notion of an integrated Baltic region within the context of a shared historical experience be described accurately. More importantly, the region has served as the border between the imperial cultures of Russia and Germany, and for the West, has always been a strong barrier against Slavonic ascendancy. Many countries share a similar geo-political marginality, but the Baltics states have had an uncommon problem in achieving and maintaining political, social and cultural sovereignty over time.

On June 15, 1940, after a brief 22 years of sovereignty, Moscow ordered 100,000 soldiers to march on the capital of Lithuania, and one day later 180,000 Soviet troops entered Estonia and Latvia. This began what Balts refer to as “Soviet Times.” At that moment in history, the annexation and occupation of the Baltic States was hardly noticed by the world, but within a year more than 85,000 inhabitants would be deported or executed. Banking, transportation, and trade industries were nationalized, and land owned by the church, private citizens, or local governments were expropriated. All existing political, economic, cultural, and professional societies were shut down, and labor unions were banned. In the natural order of authoritarian governing, magazines, newspapers and radio stations were either closed or confiscated by the state. This virtual society was also a totalitarian society, and by 1955, 2,000,000 Balts had been replaced by 1,600,000 Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarussians

The manifest end of this unnatural appropriation of the Baltic States began during the Gulf War crisis in 1990. While the world was busy with the drama of U.S. smart bombs dismantling the Iraqi war machine, Mikhail Gorbachev played his last authoritarian card – he sent in the tanks. In the end, twelve Vilnius University students and one teacher were crushed beneath Russian tank treads, defending their newly liberated television station and a people’s revolution. Their deaths, however, brought life to Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. The Soviets were gone within the year, and all three counties were free and independent once again.

“In Soviet times, we had two societies. One was a virtual society, and the other was our society. Soviet Estonia was not real, and we all knew it. But we had no power to change it, only endure it.” This is how Hagi Shein, Dean of the College of Media at Concordia International University in Tallinn, explains his world during the Russian domination before 1991 (personal correspondence, 23 June 2000). He should know he was one of the main anchors of Estonian state-run television for approximately twelve years prior to his country’s latest independence movement. “We Estonians had ways of communicating with each other. In my nightly editorial, I could always re-phrase a Soviet censored report in such a way that the people immediately understood that what I was saying was false. It was my civic duty.” (Hagi Shein, personal correspondence, 23 June 2000). Such clandestine communication prepared an entire nation for the transition to democracy and the creation of a civil society.

For much of the last century, the Balkan states of Croatia and Slovenia were under the specialized socialism of the Yugoslav Republic. In Tito’s Yugoslavia, more than 90 percent of all newspaper journalists, radio and television programmers and managers were card-carrying members of the LC, the Yugoslav League of Communists (Selnow, 2001). But by 1950 Tito’s system needed revitalization. The content of news was still formulated by the guiding hand of strict socialist policy, but radio presentations were very much westernized, and often played European and American rock n’ roll music. As it was in the Hollywood System of 1930s United States, so too did the LC powerbrokers own and control all aspects of radio broadcasting. They owned the production facilities, distribution networks, and they appointed the talent and dictated the content of radio newscasts. Yugoslav radio even accepted advertising, though it was always described as economic propaganda so that it could fall within the guidelines of Marxist doctrine (Topham, 1981).

The role of media began to change after Tito’s death in 1980 (Ruzica Vuger, personal correspondence, 16 October 2001). Everywhere in East-Central Europe there were signs of change, and during this time a coalition of leaders from the merged “nations” of south Slav peoples governed Yugoslavia and bragged about its free media (Allcock, 2000). Over time and without the strong arm of Josip Broz Tito, these disconnected Yugoslav republics, however, became more and more autonomous, and by the early 1990s each began the process of proclaiming its independence from the Federation.

Croatia and Slovenia declared their independence from the Yugoslav Federation in June 1991, and the years from 1991 to 1993 marked a period of unparalleled media development. When the new governments announced that they had changed their forms of government to a parliamentary democracy, both states also provided for a free market economy and the withdrawal of state support of public service radio and television. However, the Croat and Slovene politicians had no clear vision of what the role of media was to be in a democracy. Both states tried several plans, but the hidden agenda, according to Dr. Stepjan Malovic, was always to hold control over the most influential communications outlets, especially broadcast radio and television (personal correspondence, 25 May 2001).

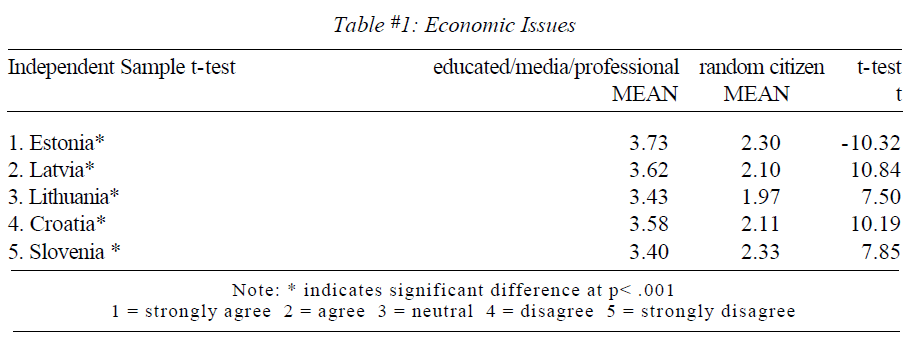

First, random citizens in all five countries felt that their country has a meaningful influence on the global economy. Additionally, random citizens perceived that private businesses in their respective countries will have a significant influence on the global economy, and persons were in favor of partnerships with multinational businesses. Finally, random citizens in all five nations assumed that globalization will have a far-reaching impact on their own economy.

Interestingly, educated, media professionals in all five countries perceived economic issues in more or less similar ways. However, they did not feel that their own country would have a meaningful influence on global economy. However, educated, media professionals agreed that their country’s partnerships with multinationals would have a bearing on the global economy. On the whole, educated, media professional did not think that their respective nations would have a meaningful impact on the global economy.

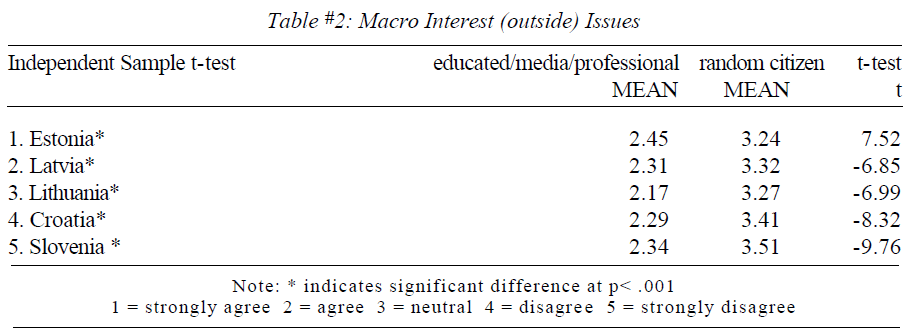

In Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Croatia, random citizens supposed that their own national interests would have an impact on globalization of media. Within that same group, these citizens felt that Russian interests would have a secondary impact of the globalization of media. However, in Slovenia, random citizens perceived that Russian interests had the greatest impact on the globalization of media, even when compared to their own national interests. In all five states, random citizens did not think that multinationals, American, or European interests would have much of an impact of globalization of media.

Educated, media professionals in all five nations, on the other hand, believed that American interests have a substantial impact on globalization of media, followed by multi-nationals. Also, they perceived that European interest would have a substantial impact on globalization of media. However, educational, media professionals in these states perceived that their own national interests and Russian interests would not have much of an impact of globalization of media. On the whole, educational media professionals in all the five nations perceived that outside interests will have greater impact on globalization of media than their own national interests.

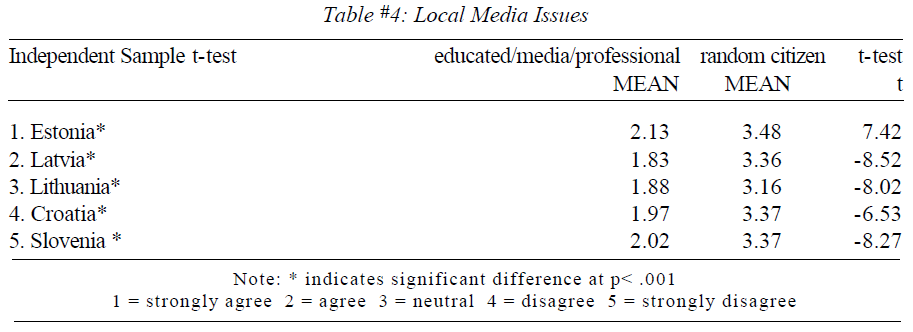

In Estonia, Croatia and Slovenia, random citizens did not recognize the effects global media might have on local media in terms of news, entertainment and advertising. However, in Latvia and Lithuania these same citizens felt that foreign media invasion would lead to a greater demand for better local news reporting. Furthermore, the same citizens did not perceive that foreign media invasion would result in a greater demand for local media to provide more entertainment choices. On the whole, in all the five states, random citizens did not perceive transnational media would affect local media in terms of news, advertising and entertainment.

Three test items attempted to measure the impact of global media on local media. In all the five states, educated, media professionals alleged that global media would have an impact on local media in terms of news, entertainment and advertising. Also, generally in all the five states, educated, media professionals perceived that transnational media would affect local media.

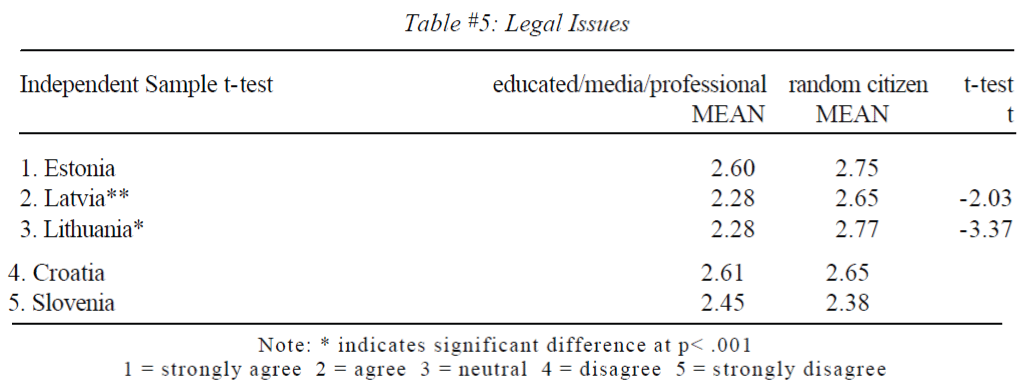

There were three items measuring perceptions on legal issues. Among the random citizens in Estonia and Latvia, there was some belief that global media would affect local governments’ rules of law, however on the whole they did not perceive global media to have any impact on their respective nation’s legal issues. Also random citizens in the remaining three nations did not perceive that global media would affect their rule of law, media laws or governing systems.

Also, there were three items measuring perceptions pf educational media professionals on legal issues. In all five states educational media professionals perceived that global media invasion would create greater demand for free speech and also would influence respective nation’s media laws. Also, in Latvia, Lithuania and Croatia, educational media professionals perceived that global media invasion would influence their governing systems. On the whole educated media professionals perceived that global media would influence their respective nation’s legal issues, more so in Lithuania and Latvia when compared to other nations.

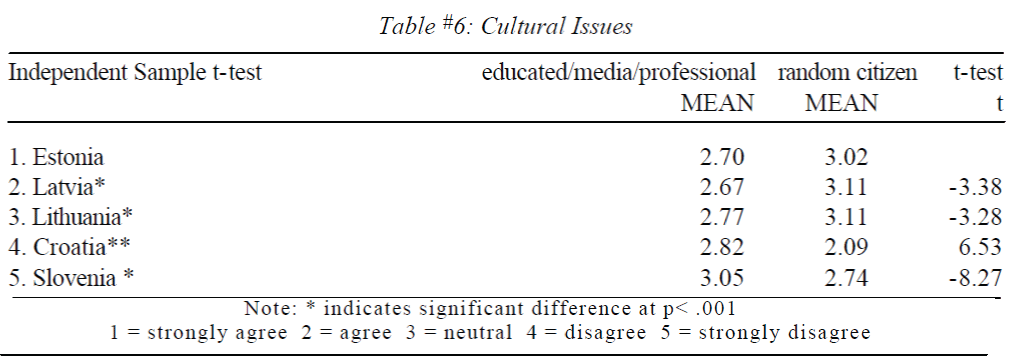

There are five items measuring cultural issues, two were positive statements and three were negative statements. The negative statements were reverse coded. Random citizens in all the five states did not perceive that global media invasion would facilitate greater understanding of other cultures. However, random citizens in these countries did not necessarily perceive global media invasion as serving “special interest groups.” Also, interestingly, while random citizens in Estonia and Slovenia did not perceive global media invasion as one-way communication process, those from Lithuania and Latvia perceived global media invasion as a one-way communication process affecting indigenous culture. On the whole, most of the random citizens in these Eastern European countries did not have any strong positive and negative perceptions when it comes to impact of global media invasion on culture.

There are again five items measuring cultural issues, two were positive statements and three were negative statements. The negative statements were reverse coded. Trends were similar in all five states. Educated media professionals in these states perceived that global media would increase greater understanding of other cultures, will help improve tolerance and also did not perceive global media invasion as a one-way communication process. Further, educated media professionals in Lithuania did not perceive global media as a system with narrowly focused agenda. On the whole, most of the educated media professionals in these Eastern European countries perceived that global media invasion will have a positive influence on cultural issue.

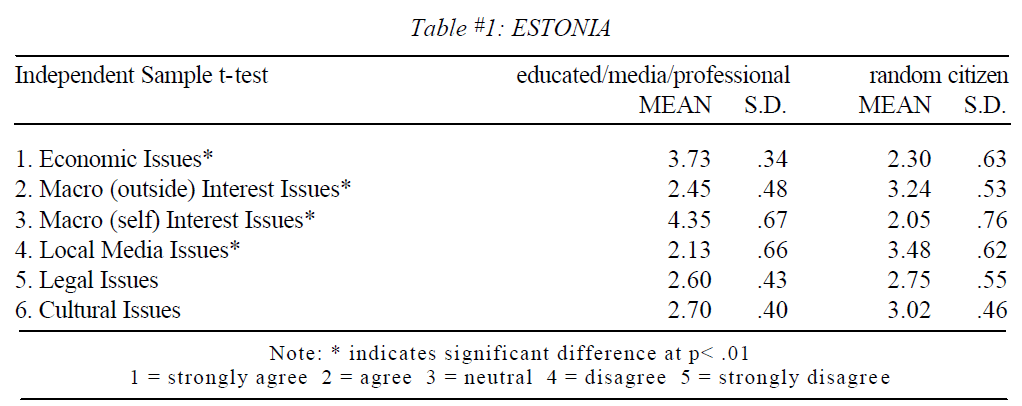

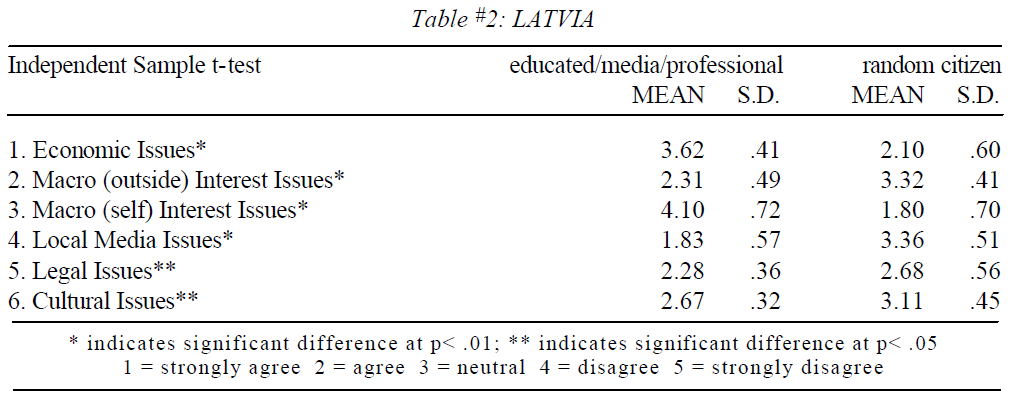

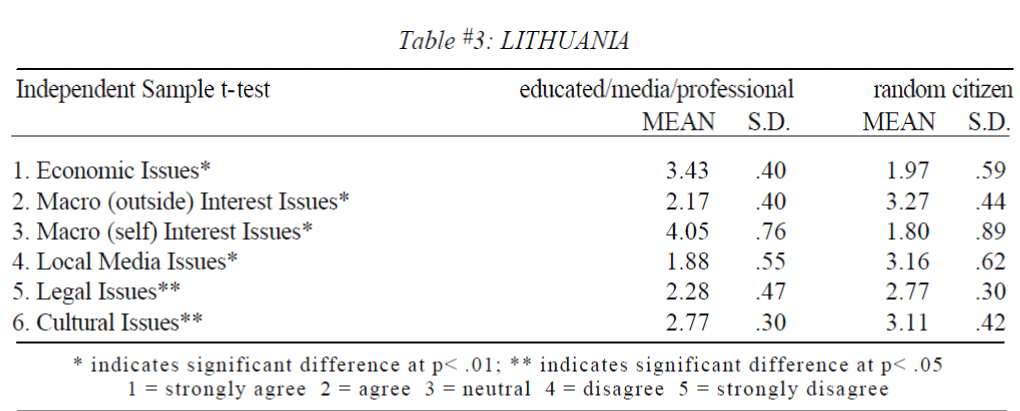

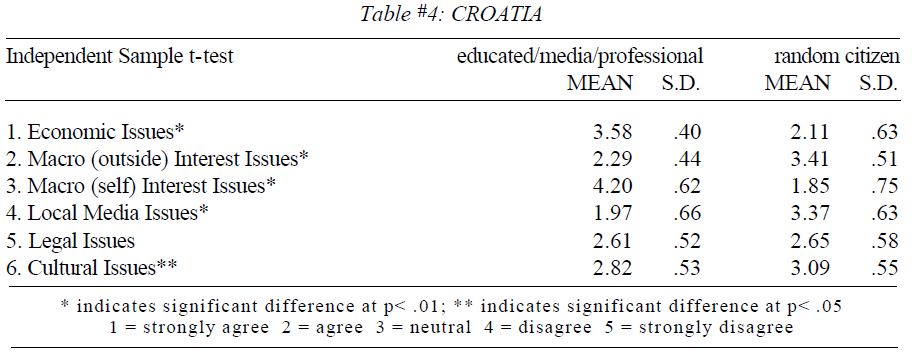

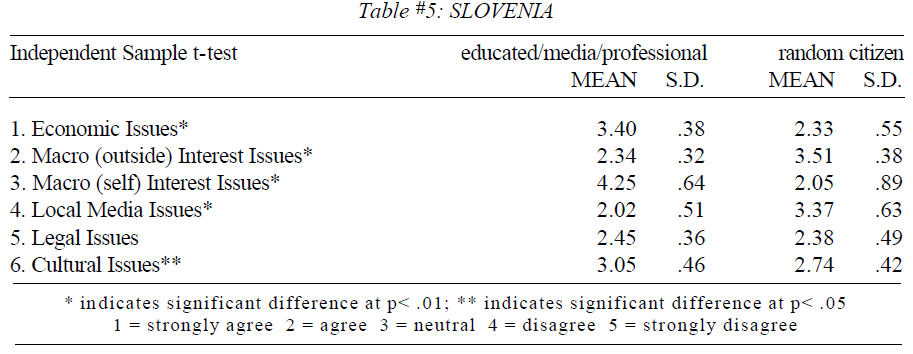

Differences between Random Citizens and Educated, Media Professionals Independent sample t-tests were conducted to see if the two groups significantly vary in their perceptions toward globalization and transnational media. In all the five states, educated media professionals, and random citizens significantly differed in their perceptions toward how globalization would affect economic issues. While educated media professionals did not perceive that their respective nations will not meaningful influence on the global economy, random citizens perceived that their respective nation influences national economy.

The two groups also significantly vary in their perceptions of macro interests of globalization and transnational media. In all the five states, educated media professionals and random citizens significantly differed in their perceptions in terms of whose interests make a substantial impact on the globalization of media. While Educated media professional perceived that outside interests (especially, American and multinational interests) would influence the globalization of media, random citizens did not perceive that outside interests have a substantial impact on the globalization of media , there was a significant difference in all the five states.

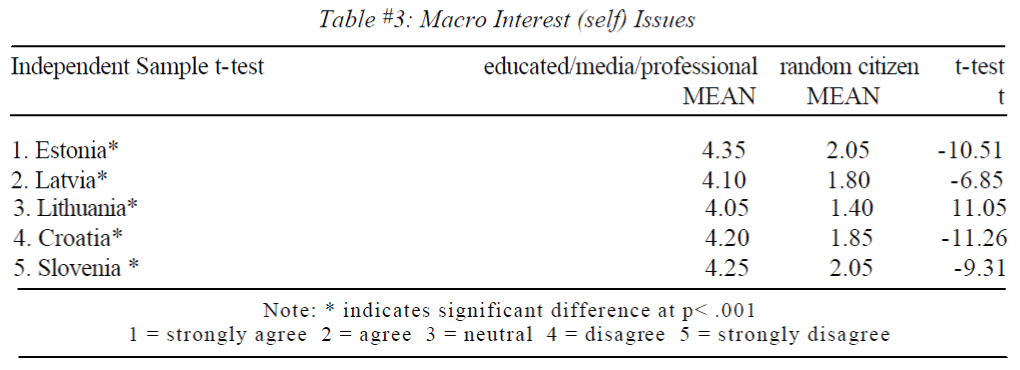

Similarly, While educated media professionals did not perceive that their respective national interests would meaningful influence globalization of media, random citizens perceived that their respective national does in fact influence the globalization of media , there was a significant difference between the two groups in all five nations.

Independent sample t-tests were conducted to see if the two groups significantly vary in their perceptions on how transnational media would affect local media. In all the five states, educated media professionals and random citizens significantly differed in their perceptions on how global media would affect local media While educated media professionals perceived that their respective nation’s local media in terms of news, entertainment and advertising will be affected by global media, random citizens perceived other wise, further, there was a significant mean difference between the two groups.

Independent sample t-tests were also conducted to see if the two groups significantly vary in

their perceptions on how transnational media would affect legal issues. In Estonia,  Slovenia and Croatia, educated media professionals and random citizens did not significantly differed in

their perceptions on how global media would affect legal issues. Educated media professionals and

random citizens perceived that their respective nation’s legal issues in terms of free speech, and media

laws will be affected by global media,

Slovenia and Croatia, educated media professionals and random citizens did not significantly differed in

their perceptions on how global media would affect legal issues. Educated media professionals and

random citizens perceived that their respective nation’s legal issues in terms of free speech, and media

laws will be affected by global media,  there was a no significant mean difference between the two

groups. However, in Latvia and Lithuania, educated media professionals and random citizens

significantly differed in their perceptions on how global media would affect legal issues. In other words, educated media professionals in these countries more

significantly perceived that global media would affect legal issues when compared to random citizens.

there was a no significant mean difference between the two

groups. However, in Latvia and Lithuania, educated media professionals and random citizens

significantly differed in their perceptions on how global media would affect legal issues. In other words, educated media professionals in these countries more

significantly perceived that global media would affect legal issues when compared to random citizens.

Independent sample t-tests were also conducted in this case to see if the two groups significantly vary in their perceptions on how transnational media would affect cultural aspects. In Estonia, educated media professionals and random citizens did not significantly differed in their perceptions on how global media would affect cultural issues. Educated media professionals more than random citizens perceived that their respective nation’s cultural issues would be affected by global media invasion, however there was a no significant mean difference between the two groups. However, in Latvia, Lithuania, Croatia and Slovenia educated media professionals and random citizens did significantly differed in their perceptions on how global media would affect cultural issues. Interestingly, in Latvia, Lithuania and Croatia, educated media professionals more than random citizens perceived that their respective nation’s cultural issues would be affected by global media invasion. However, in Slovenia random citizens more than educated media professionals perceived that their respective nation’s cultural issues would be affected by global media invasion.

For a researcher working within a society that has been recently “freed” from totalitarian rule unique complications are everywhere. The challenge of political sensitivities, the reluctance of governments to disclose financial information, the issues of regional competitiveness, or the fears of phobic citizenry complicate the data gathering process. Obtaining believable results is difficult at best, and often unworkable. This is especially true of the Balkan states, which are yet to recover from a brutal war that lives on in the minds of its citizens. However, most of the peoples of Eastern Europe have embraced the idea of becoming a modern sovereign state within the European Union. The five sovereign states that are the subject of this inquiry, like many other states in the region, remain states in transition.

The current investigation emerged from case study analyses of transitioning mass media in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Croatia, and Slovenia. These case studies centered the process of how societies in Eastern Europe were changing their forms of government from dictatorship to democracy, and how the changeover affected their public-service broadcasting systems, which was also affected by the tectonic shift of human affairs known as globalization. The use of the case study methodology as a tool of inquiry limits researchers in drawing generalizations about the subject studied, but because the subjects considered are unique phenomena, new hypotheses arise naturally and researchers may, as a result, posit atypical, theoretical questions about that field of study.

One outcome of this research has implications for future inquiry. Evidence has emerged from the survey of 200 citizens of five Eastern European states that points to some new ideas about communication theory and the constructs of modernity. Today, most human societies are greatly affected by globalization and are evolving towards modernity in similar ways, and the emergence of transnational media as the leading marker of societies in transition is clearly indicated. Therefore, theories of mass communication are integrated with the sociological tenants of modernity, which play and important role in all communication theories. These researchers call this new hypothesis an Integrated Theory of Mass Media and Modernity, which has its roots in the social theory of mass society described by the 19th Century sociologist, Ferdinand Tonnies. Tonnies described two basic societies: the “traditional” and the “urban-industrial” society. Clearly, there is a third type, the “transitioning society,” which is in the process of restructuring its fundamental institutions. Points of argument for an Integrated Theory of Mass Media and Modernity include:

• Classical sociology describes modernity as consisting of two distinct societies: the “traditional” and the “urban-industrial society.” There is a third – it is called the “transitioning society;”

• A transitioning society is in the process of restructuring fundamental institutions: from a centralized to a free market economy; from an authoritarian government to a democratic government; from ethnocentrism to pluralism; from politically controlled media to unregulated media; from autocratic rule to the rule of law;

• The stress caused by the loss of traditional values and the acceptance of modern values is exacerbated by an invasion of transnational (and foreign) mass media;

• Globalization, a powerful consequence of modernity, is seen by the transitioning population as a form of cultural and commercial imperialism;

• Opinion Leaders in these societies use globalization and media invasion as tools for rallying society (ethnicity, nationality, citizenry) against the passage to modernity;

• Modernity may or may not be the certain outcome of transitioning societies.

It should be obvious that such speculations must be tested before any claims can be made as to their validity. But an explanation-building strategy has been employed in this qualitative investigation and “theory-building” is an appropriate outcome of such inquiry. The basic assumptions posited by this “integrated theory of mass media and modernity” must be studied, and the results analyzed and questioned by communication scholars worldwide.

Copyright © 2025 Global Media Journal, All Rights Reserved