ISSN: 1550-7521

ISSN: 1550-7521

Orayb Najjar*

Dept. of Communication Northern Illinois University DeKalb, IL 60115

Visit for more related articles at Global Media Journal

Using Pierre Bourdieu’s Field Theory, especially the concept of the interconvertability of cultural, economic, political and media capital, I examine the rise of regional and global centers of broadcasting that seek to compete with the CNN and the BBC, namely, TeleSUR of Latin America, Al-Jazeera Arabic, and Al-Jazeera International (AI) of Qatar (launched worldwide on November 15, 2006). I also describe the Latin American and Arab questioning of the inevitability of following “the Anglo-Saxon” model of “commercialization, depolitization and trivialization of news.” I examine the countermeasures the U.S., British and French governments are taking to fend off this regional and global competition from Latin American and Arab media.1 I conclude that diversity and the expansion of the news pie is a healthy phenomenon that is bound to help serious news gathering and reporting worldwide against the rising trend of infotainment that has started to taint serious news dissemination in the United States.

“Television is a window on the world. But if you are sitting in Latin America, that window is more likely to be facing Baghdad than Buenes Aires. Or show Michael Jackson instead of Mexico City. Or offer a clearer view of Ukraine’s Orange Revolution than the one in Ecuador last month. Those networks do not cover regional news, like CNN Espanol, based in Atlanta, or Spain’s TVE, are often considered US or Eurocentric, with pundits sitting in Washington or Madrid. (Harman, 2005, p. 1).

“We launch Telesur with a clear goal to break this communication regime and present a vision, a voice which until now has been silenced. Telesur is an initiative against cultural imperialism.” Andres Izarra, TeleSur president and Venzuela’s minister of communications (Latin America TV takes on US Media, 2005, p. 1).

“Al-Jazeera International is 'the most exciting television news and current affairs project in decades -- one which will revolutionise the global news industry by offering viewers across the world a fresh perspective on news.” (Nigel Parsons, managing director of Al-Jazeera International) (A correspondent, 2005, p. 1).

Bourdieu (1998: 41) suggests that for a journalistic field analysis to be complete, “the position of the national media field within the global media field would have to be taken into account.” The dissatisfaction with Western news sources has a long history and dates back at least to the era of primacy of Western news agencies on the world news scene. NWICO discussions at UNESCO in the 1970s and 1980s provided “Third World” countries with a forum in which they complained about the unequal flow of information that moved mostly from North to South and from West to East. The impetus for the creation of alternatives to Western media, then, as now, was fueled by dissatisfaction with media’s content, its narrow focus, its lack of source diversity and the absence of serious attention to the news of the rest of the world.

Decades later, the problems became worse. In the United States of the mid-1990s, television networks gave much less attention to serious foreign news than during the Cold War years. CBS maintained 24 foreign bureaus in its heyday; by 1995, it had reporters in only four capitals (Hess, 1996, 66). In the 1970s, the networks in the US ran as much as 45% foreign news. By 1995, the proportion was in the teens (Bierbauer, 2006).

American newscasts also tend to be ethnocentric in their selection of news sources. Only 14 of the 401 guests who appeared in "Meet the Press" (NBC), "Face the Nation" (CBS) and "This Week with David Brinkley" (ABC) in 1994 were foreigners (Griffith, 1986, p. 72 in Hess, 1996, p. 7). During the first four months of 1995, foreign stories added up to 10 percent of the news segments, ranging from 3 percent on NBC’s "Today" to 16 percent on ABC’s "Good Morning America" (Stephen Hess, Telephone Interview with Tyndal on July 11, 1995). McGuiness examined 139 transcripts of three news talk shows, November 27, 2005-November 5, 2006, to see if sourcing practices had changed. She found that only four foreign experts were consulted in 47 programs of “This Week with George Stephanopoulos” even though 77 percent of the programs under study had a foreign angle. Although 122 guests by the Stephanopoulos show, only four of them were foreign. In “Face the Nation,” although 28 out of the 41 transcripts examined had a foreign angle, only two foreign experts were included in the programs. In “Meet the press,” even though 35 out of 51 shows had a foreign angle, only four foreign experts were consulted (McGinnis, 2007).

The Monroe Doctrine of 1823 declared Latin America as a U.S. sphere of influence and was recognized as such internationally. So it is not surprising that the U.S. established a media presence there. The three United States networks, NBC, CBS, ABC, sought to establish their broadcast dominance in Latin America through the development of the media and the purchase of shares in TV stations. ABC international, formed in 1959, invested in five Central American stations in what it called, “Central American TV Network,” (CATVN) (Wells, 1972, p. 104; Frappier, 1969, p. 4)

By 1968, Worldvision of ABC operated in sixteen Latin American countries and broadcast to an audience of more than 20 million households (Frappier, 1969, p. 3).

NBC-TV has provided technical and financial assistance to televisions in Argentina, Mexico, and Venezuela and provided programs dubbed into Spanish in Mexico City (Skorinia, 1965, p. 187; Wells, 1972, 103). CBS had various partnership arrangements in television centers in Argentina (Skornia,1965, 187) and interests in production companies in Peru, Argentina-and Venezuela (Frappier,1969, p. 10).

The Latin American markets are owned by Global corporations that have also entered many markets in Latin America, partnering with local conglomerates. Two Spanish corporations, Telefónica and Grupo Prisa, have acquired media outlets in several countries. Grupo Prisa has purchased most of the shares of Caracol Radio in Colombia, and Telefónica owns television and radio stations throughout the region (Ketupa.net, 2005).

Major Latin American media groups have "gone global" (whether through alliances or through direct investment) because the most lucrative markets for their products lie outside the region. The global Spanish-speaking market, for example, is as large as 330 million consumers - of which 24 million are located in the US and 39 million in the EU (principally in Spain). Revenue from the US and Spain dwarfs those of domestic markets: peak audience figures are found within Latin America but the big money comes from sales to overseas (Ketupa.net, 2005). Thus, the content of those global corporations is not entirely local, and the problems U.S. networks and cable channels are experiencing in providing meaningful content have been globalized.

“The State of the News Media 2006: An Annual report on American Journalism Project for Excellence in Journalism” funded by the Pew Charitable Trusts, noted that time slot rather than network type seems to define news judgment in the three networks. The report found that morning news programs build stories around emotion, and even tell viewers how to feel about a story by using emotive language (“shocking … horrific …brutal”). On the day news was examined, May 11, the commercial evening newscasts were so strikingly similar to each other that the first 12 minutes of news time on the three programs covered the same stories.

The report found that morning news are interview-based programs, with a “softer” news agenda that provided a more limited range of sources and viewpoints than many other media. Evening news went more deeply into issues and contained more news sources than morning news or cable.

The report also noted that opinion was more restrained in evening news. On May 11, 32% of commercial evening news stories contained reporters’ opinions. Less than morning news (48%) or cable (45%), but still substantial. Cable did not get a break from the researchers. The report added that while some cable companies like Fox were gaining audiences over network TV, their content lacks professional standards:

For the third straight year, our content analysis of cable suggests that it is thinly reported, suffers from a focus on the immediate, especially during the day, is prone to opinion mongering and is easily controlled by sources who want to filibuster (The State, 2006).

And since most Latin Americans get a large share of their news from the United States, they, too, get exposed to that type of news. As a result, international news from the Latin American perspective is almost nonexistent, critics say. But, says journalist Aram Aharonian, one of TeleSur’s founders, ‘not for long’” (Harman, 2005, p. 1). More than 40 private television stations and 128 cable channels are operating in Venezuela, of those, only two are public broadcasting channels (Giordano, 2005, p. 15). TeleSUR wants to change that.

This study aims to understand the significance and implications of the lack of trust in formerly dominant Western media corporations broadcasting to Latin America and the Middle East, and describe the rise of new types of regional media like TeleSUR of Latin America and Al-Jazeera Arabic and Al-Jazeera International (AI) of Qatar.

After laying out the conceptual framework by using the concept of “field” as developed by Pierre Bourdieu and utilized by others, I describe the latest developments in regional and global broadcasting by applying the relational concept among fields to examine how the fields of economics, politics and media interact, and by describing how the concept of the interconvertibility of fields affects the media. I then analyze the implications of these complex relationships by examining the competition between “old media” (i.e., CNN, the BBC and European and American media) and “new media” (i.e., TeleSUR of Latin America and Al-Jazeera International) from a professional perspective suggested by field theory. I end by describing what the “old media” are doing to compete with the “new media,” and then discuss what that ferment means for global broadcasting.

After the privatization of the largest French television channel in 1986, Benson & Neveu (2005) noted that the French experienced side effects long taken-for-granted by “anglo-saxons” – “sensationalized, depoliticized and trivialized news.” The change led to French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s impassioned public intervention in a book called On Television, which “served as a wake-up call for many around the world that there was nothing ‘natural’ about an advertising saturated, audience-ratings-driven media culture” (Benson & Neveu, 2005, p. 3). Many practitioners in media systems under study in Latin America and the Arab world agree with that assessment and see the new media they are introducing as an alternative to that model. “For me,” says Blanca Eekhout, adviser on the establishment of TeleSur, “it’s indispensable for communities to have in their hands channels of communication which are their own. And what’s more, this had to have an international aspect” (Venezuela sets up ‘CNN rival’, 2005, p. 4).

field may be viewed as a microcosm that brings together the agents and institutions engaged in the production of whatever that particular field produces; e.g. literary works in the literary field, or articles in the journalistic field. Members of a field both constitute it, but also are constituted by it. They represent the field to themselves as well as to others. Professionals who share a field are constrained by the forces inscribed in it, but are also able to act, “in ways that are partially preconstrained, but with a margin of freedom” (Bourdieu, 2005 p.30 in). The essence of field theory in the social sciences is the explanation of regularities in individual action by using the position of an agent within a given field vis-à-vis other fields (for example, the position of the journalistic field in relation to the political field) (Martin, 2003). “In analytic terms, a field may be defined as a network, or a configuration, of objective relations between positions” (Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992, pp. 96-97). The journalistic field is important because it is seen as part of the field of power; that is, it tends to engage with powerful agents who possess high volumes of what Bourdieu calls “economic and cultural capital,” both of which are important forms of power (Bourdieu, 2005, p. 33). By economic capital, Bourdieu means money or assets that can be turned into money. Cultural capital includes educational credentials, technical expertise, general knowledge, verbal abilities, and artistic sensibilities. The social world is structured around the opposition between these two forms of power, with economic capital, on the whole, being more powerful (Bourdieu, 2005, p. 55). Inside the journalistic field, economic capital is expressed via circulation, or advertising revenues, or audience ratings, whereas the “specific” cultural capital of the field takes the form of intelligent commentary, in-depth reporting, -- the kind of journalistic practices rewarded each year by Pulitzer Prizes. Each field is thus structured around the opposition between the pole representing forces external to the field (primarily economic, e.g. advertising) and the “autonomous” pole representing the specific capital unique to that field (e.g., artistic or scientific skills). Fields are arenas of struggle in which individuals and organizations compete to valorize those forms of capital which they possess (Benson and Neveu, 2005, 4). Perhaps the most important quality of fields for this paper is the interconvertability of capitals. Since the structure of fields is characterized by the dynamic relationship between symbolic and economic assets, at any given moment some fields move closer to the economic end of the pole than others; i.e., the knowledge they produce is simply more convertible into material or political power than the products of other fields (Lenoir, 1997; Graham, 1998).

Field theory positions itself precisely between political economy and cultural approaches that link news production directly to the interests of broad social classes or the national society, and organizational approaches that focus too narrowly on particular news producers. “Field research thus calls for the examination of ‘institutional logics’: the simultaneous analysis of social structures and cultural forms, as well as the complex interplay between the two” (Benson and Neveu, 2005, p.12). Benson and Neveu suggest that in field theory, journalistic fields do not always reinforce the power status quo, but under certain conditions may actually transform power relations in other fields (2005, p. 9). “To think in terms of field is to think relationally” (Benson & Neveu, 2005, p. 3). The relational approach of field theory is important for this analysis because it helps us “locate, situate, and explain the very real differences among media outlets according to their possession of different types and quantities of capital” (Benson and Neveu, 2005, p.19).

Field theory is especially useful for studying international journalistic organizations comparatively because it provides a means of incorporating history into media analysis. Field theory provides perhaps the best defense against “media-centrism,” helping situate journalism in its larger systemic environment, rather than restricting the study to its organizational features, such as funding, ownership, demographics of journalists and audiences. Against the fruitless question of whether the press is or is not “independent,” research could help pinpoint the journalistic field’s relative position vis-à-vis the range of other societal fields that compete to shape our vision of the social world (Benson and Neveu, 2005, p.19; Benson, 204, p. 276). Finally, Bourdieu’s theory takes power dynamics seriously, both within and among fields. As a result, field analysis places greater emphasis on competition and distinctions among journalists, and thus pays greater attention to such social phenomena as competition over scoops, struggles over access to sources, changes in the relative prestige of news organizations, in short, to the “relational” construction of journalistic identity (Benson and Neveu, 2005, p.18).

Taking its cue from Hallin and Mancini, both of whom have used the concept of “field” in their research, this study avoids measuring media systems against normative ideas (as in the Four theories of the Press), but analyzes “their historical development as institutions within particular social settings … to understand why they developed in the particular ways that they did; what roles they actually play in political, social, and economic life; and what patterns of relationships they have with other social institutions” (Hallin and Mancini, 2004, p. 14). Translating those insights into research questions leads to the following:

Research Question I: How did TeleSur develop as an institution and what was the effect of the social setting in which it developed on its developmental trajectory?

Research Question 2: How do journalistic organizations like TeleSur and Al-Jazeera International exert influence on one another and on other journalists in ways that supplement or contradict constraints emerging within the single newsroom? In what ways do these two organizations resist or reshape outside economic and political pressures and national cultural idioms?

Research Question 3: What is the Latin American and Arab journalistic field’s relative position vis-à-vis the range of other societal fields that compete to shape the vision of the social world?

Research Question 4: How does Al-Jazeera International plan to compete in the regional and global arenas? What patterns of relationships has it developed with other journalistic institutions?

The first research question inquired how TeleSUR developed as an institution and wondered how its social setting affected its developmental trajectory.

Media ownership patterns in Latin America had a great bearing on the way TeleSur developed. In Mexico and Brazil, media conglomerates such as Televisa and Globo, respectively, have consolidated their control, particularly in broadcasting, although they also own companies in print, music, and radio. Grupo Clarín in Argentina, Organización Carlos Ardila Lule and Grupo Empresarial Bavaria in Colombia, and Grupo Cisneros in Venezuela clearly dominate the media markets in their countries. Elsewhere in Latin America, media outlets are typically controlled by a handful of family-owned companies that are frequently tied to political parties or corporations (Lauria, 2003). The aim of TeleSur was to break free of that monopoly.

Televisora del Sur, Spanish for "Television Station of the South", named TeleSUR, is a pan-Latin American television network based in Caracas, Venezuela. It began broadcasting on a limited schedule on July 24, 2005 and began full-time broadcasts on October 31, 2005 (Telesur en canal, 2005).

TeleSUR was intended to be a counterweight to popular privately-run networks in South America like CNN en Español and Univisión, and BBC World. The key to TeleSUR's success is not going head-to-head against the giants of broadcasting but providing an alternative to what Aram Aharonian calls, “the hegemonic communications industry that has one way of thinking and one message" (Marx, 2005).

What all fields like politics, sociology and journalism have in common, says Bourdieu, is that “they all lay claim to the imposition of the legitimate vision of the social world” even when they do not admit that all categories are socially constituted and socially acquired (Bourdieu, 2005, 36). What the media do is crucial to politics, says Bourdieu, because “Politics is a struggle to impose the legitimate principle of vision and division, in other words the one that is dominant and recognized as deserving to dominate, that is to say, charged with symbolic violence” (Bourdieu, 2005, 39).

Aram Aharonian, main director of the station, wants TeleSUR to defy “the dominant hegemonic media culture through its motto ‘Our North is the South,’ a play on the UNESCO debates of the 1970s (Victoria, 2005). The station can be seen in at least 15 countries through at least 53 cable services, as well as five free stations. TeleSUR runs public service announcements and musical interludes instead of commercials. The news channel has 160 employees and correspondents in Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia, Cuba, Haiti, Mexico, Uruguay and the United States (TeleSUR Concepto, 2005). TeleSUR’s area of coverage extends from Tierra del Fuego to Canada, reaching 370 million Hispano-Americans, 180 million Brazilians, over 50 million Latinos in Chicago (Dos Reis, 2005). But whether those people will watch remains to be seen.

Telesur went on air July 24, 2005. With Venezuela as a majority shareholder, it is financed jointly by the governments of Argentina, Uruguay and Cuba, with some support from Brazil (Brazil TV International) (Dos Reis, 2005). The driving force behind the station has been President Hugo Chavez, whose government has contributed 70% of Telesur's $10m (£5.7m) financing and owns 51% of the channel (Green Left Weekly, 2006). The station is trying to develop talent from all over Latin America. Sixty staff members have been recruited from different countries. All the shows will be produced by Latin Americans, except some contemporary independent films dubbed Nojolivud (No Hollywood) (Daniels, 2005).

The relational approach of field theory is important for this analysis because it helps us “locate, situate, and explain the very real differences among media outlets according to their possession of different types and quantities of capital” (Benson and Neveu, 2005, p.19). Here, the difference between TeleSUR and Al-Jazeera is clear, and may be explained by each station’s possession of different types of capital. While Al-Jazeera possesses enormous political and cultural capital because it is seen as very critical of Arab leaders, some find that the perception of TeleSur as being too close to the government of President Hugo Chavez, rightly or wrongly, will hamper its ability to attract viewers in a region traditionally distrustful of state-run institutions (Sreeharsha, 2005, p. 1). The fact that Chavez has enacted new media laws that limit speech by commercial companies also did not endear him to his critics or to some human rights activists.

The second research question sought to determine how journalistic organizations like TeleSur and Al-Jazeera International exert influence on one another and on other journalists in ways that supplement or contradict constraints emerging within the single newsroom. Of interest was the ways in which the two organizations resist or reshape outside economic and political pressures and national cultural idioms.

The success of Al-Jazeera in loosening the monopoly of the West on international news dissemination has been watched with rapt attention in Latin America and elsewhere.

From the beginning, TeleSur was compared to Al-Jazeera. A journalist writing for the Christian Science Monitor titled a section of his/her article, “Latin America’s Al Jazeera?” (Harman, 2005, p. 2). Another writing for the BBC wrote that “Some have already dubbed it Al-Bolivar – a combination of the Arabic news channel, Al-Jazeera, and President Hugo Chavez’s favourite [sic] independent hero” (Bruce, 2005, p. 1).

The founders of TeleSUR appear to understand the interconvertablilty of fields; the fact that economic assets can be translated into political assets, as Bourdieu has observed. TeleSUR helped reshape economic pressures by recognizing that one powerful well-funded station is much more effective than many alternative stations. Aram Aharonian, general director of the channel, is aware that funding is “an important political act. Instead of having 500 or 900 small alternative media outlets, there will be one grand conglomerate. With capital. … Telesur will follow the same premises that for decades took refuge in small alternative and community media. But now we have left our marginal niche and are heading towards mass communications” (Jordana, 2005, p. 3).

Not everyone in Latin America thinks this is a good idea. Alberto Ravell of Globovision says that the station will transmit a view of Latin America, but “you’re going to have the view these governments want you to have, not an impartial view,” a leftist view because all the people working at TeleSur are leftist (Bruce, 2005, p. 4). Connie Mack, a member of the House International Relations Committee and an outspoken Chavez critic was alarmed when the Al-Jazeera signed an agreement with the Latin American news channel TeleSUR for "cooperation in training and the exchange of footage and logistics" (Al-Jazeera Network on Air, 2005). Mack stated that:

When Hugo Chavez launched Telesur last year to spread his anti-freedom rhetoric throughout Latin America I raised numerous concerns that he was creating a TV network patterned after Al-Jazeera. Today, Hugo Chavez has gone even further. … Now he’s in cahoots with the original terrorist TV (Mack, 2006).

Al-Jazeera Arabic continues to resist international and especially U.S. efforts to silence it, local pan-Arab pressures to censor it, and efforts to starve it of advertising funds. It does so, by following professional norms of journalism other journalists (if not their governments) recognize.2 Al-Jazeera Arabic tries to resist financial pressures by attempting to lure advertisers to the Sports Channel and children’s channels with no political content because advertisers shy away from what they consider controversial programs despite Al-Jazeera’s superb demographics (Khanfar, 2004, p. 3).

TeleSUR resists political and economic pressures and denies accusations that it is supported by the state. TeleSUR is attempting to get outside sources of funding, not for ads, but for spots from sponsors like those run on PBS (Jordana, 2005, p. 4). Furthermore, Chavez’s supporters claim that the bad blood between Chavez and mainstream media came about when Chavez forced TV stations to pay taxes just like other businesses. Not only did Chavez tax those businesses which had allowed previous rulers of Venezuela to place censors in their offices in return for being tax free, but Chavez himself, a consummate communicator, became the media by hosting a weekly show called “Allo Presedente!” Chavez’s admirers are quick to point out that the show, unlike George Bush’s weekly radio address, is not a monologue. Chavez, they say, brings several secretaries to hear and jot down the details of people’s problems and returns a week later to announce how those problems had been solved (Al Giordano, 2005, p. 9).

Al-Jazeera’s success has spawned a number of imitators in the form of pan-Arab satellite channels that have introduced a similar type of news reporting, leading Al-Jazeera to want to reinvent itself to separate itself from the rest (Khanfar, 2004, p. 1). The station has expressed a renewed commitment to reporting, and a move away from depending solely on the talk shows that made it famous (Schleifer, 2004, p. 3).

The May 2006 week-long reporting from China was so successful that Al-Jazeera is going to India in recognition of the importance of that populous country. Al-Jazeera has signed a cooperation agreement with China Central Television (CCTV). The partnership covers three areas: news and image exchanges, non-news program exchanges, and cross-company staff training. Al-Jazeera will also sign cooperation agreements with Xinhua News Agency and China International Radio in the near future. Al-Jazeera’s Beijing office will be expanded in a few weeks and a Chinese channel will be launched on Al-Jazeera's website (Wan, 2006).

But its most ambitious move was establishing an English-language station that competes with the Western media in English-speaking countries. Waddah Khanfar hopes that advertisers will patronize it “because this niche is beyond regional politics and their unfortunate effects” (Khanfar, 2004, p. 3).

The third research question in this paper sought to discover the Latin American and Arab journalistic fields’ relative position vis-à-vis the range of other societal fields that compete to shape their vision of the social world.

Field theory suggests that members of a field both constitute it, but also are constituted by it. TeleSUR, even while introducing a revolutionary project, could not move away from the tenets of global journalism and from the negative perception of media owned by government. Because the idea for Telesur was initially proposed by Cuba’s President Castro (Jordana, 2005, p. 6), and because the station’s critics were already calling it “Telechavez” even before it went on air, the station had to work to “unbrand” itself by moving away from a political field funded by the president of Venezuela, to an independent field similar to Al-Jazeera; i.e. funded by the ruler but whose board of directors is independent.

Real power inside TeleSUR will rest on a seven-member board of directors led by [then] Venezuela's communications minister, Andres Izarra (Green Left Weekly, 2006). Telesur president Andres Izarra stepped down as information minister when one of the well-known board members, English novelist and filmmaker Tarik Ali, said publicly that for the station to be truly effective it would need to be entirely independent. Izarra, who had previously worked for NBC's defunct Canal de Noticias NBC, CNN and Radio Caracas Television, a private Venezuelan network, knew that he needed to step down. TeleSUR's advisory council tells volumes about its ideological orientation. It includes Latin American as well as international intellectuals who have spoken about Western hegemony and called different ways of organizing society.3 None of them is likely to accept intervention by any government because they understand that legitimacy of the journalistic field demands that kind of separation. TeleSUR's current president, Andrés Izarra, agreed that once the station is on air, it needs to distance itself from the Venezuelan government “in order to guarantee that it complies with its aims and ethical standards” (Telesur keen on Aljazeera link up, 2005, p. 2). The founders of the station asserted their independence from the Venezuelan state administratively without distancing themselves from the station’s revolutionary purpose. Aram Aharonian is open about TeleSUR’s being “a strategic project that was born out of the need to give voice to Latin Americans confronted by an accumulation of thoughts and images transmitted by commercial media and out of the urgency to see ourselves through our own eyes and to discover our own solutions to our problems. If we do not start there, the dream of Latin American integration will be no more than a salute to the flag” (Jordana, 2005, p. 2).

Members of a field also represent the field to themselves as well as to others. To themselves, they presented what they have accomplished as “Media from Below” fighting “media from above.” TeleSur’s supporters also claimed that commercial media and the U.S. government saw Venezuela’s access to its own pan-Latin American media as “something akin to Venezuela developing the atomic bomb” (Giordano, 2005, p. 1). As noted above, professionals who share a field are constrained by the forces inscribed in it, thus the need to establish the independence of the station. Independence would free TeleSUR to act in creative ways, or, as field theory would put it, “in ways that are partially preconstrained, but with a margin of freedom” (Bourdieu, 2005 p.30 in). The station has asserted its production independence from big conglomerates that own media in Latin America and created a new model that favors local talent; one they have dubbed, “No Hollywood.”

Fields are arenas of struggle in which individuals and organizations compete to valorize those forms of capital which they possess (Benson and Neveu, 2005, 4). The journalistic field is important because it is seen as part of the field of power; that is, it tends to engage with powerful agents who possess high volumes of what Bourdieu calls “economic and cultural capital,” both of which are important forms of power (Bourdieu, 2005, p. 33).

By tapping into the Arab public need for pan-Arabism and the need to speak truth to power (not available before the age of satellites), Al-Jazeera has succeeded in increasing the capital it possesses by amassing both political capital “the power of consecration” and cultural and symbolic capitals. Its experts, drawn from 22 Arab countries and all over the world, present a formidable challenge to Arab rulers. Arab experts comment on the foibles of their rulers and invite viewers to do the same via live phone calls and written commentary on different programs. And while almost every single Arab country had banned Al-Jazeera at one time or another, and while some (like Saudi Arabia) refuse to let it establish bureaus in the country, the station remains the most watched and respected Arab station, with about 50 million viewers. Yet, Al-Jazeera has failed to convert its important cultural capital into economic capital because of the boycott imposed against the station by Saudi Arabia and Kuwait; nations who control the Arab advertising markets, and by American corporations.

Benson and Neveu suggest that in field theory, journalistic fields do not always reinforce the power status quo, but under certain conditions may actually transform power relations in other fields (2005, p. 9). In the case of Al-Jazeera Arabic, the station has succeeded in changing power relations by privileging the media over Arab rulers, and by making itself indispensable for Arab political deliberations. Telesur staffers agree that some things are non-negotiable: nothing against regional integration or the struggle against neo-liberal globalization.” (Jordana, 2005, p. 4). Enrique Botero, a Columbian television producer, referred to an old US comic, Lucky Luke, a cowboy who sells protection to a journalist who heads a small paper whose motto is, “independence always, neutrality never” (Jordana, 2005, p. 5).

The fourth research question attempted to determine how Al-Jazeera International plans to compete in the regional and global arenas. Specifically, it sought to determine the patterns of relationships it has developed with other journalistic institutions.

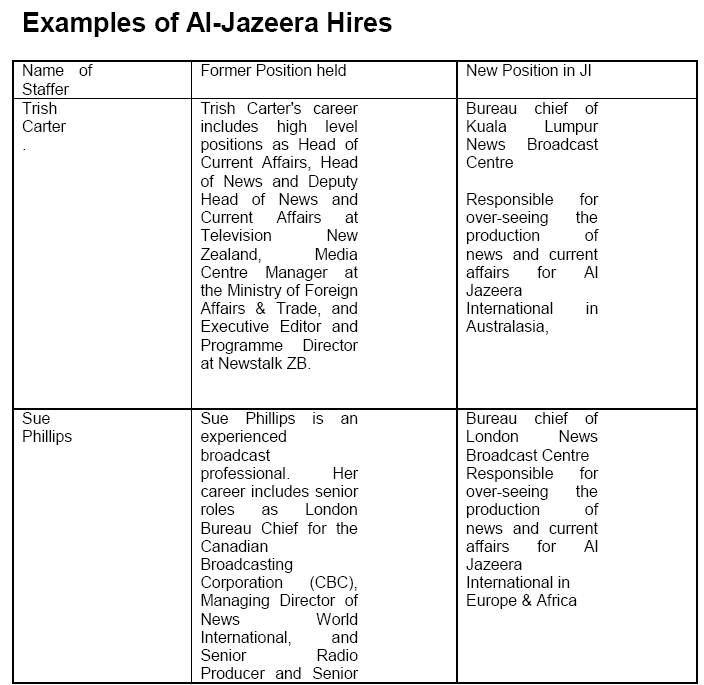

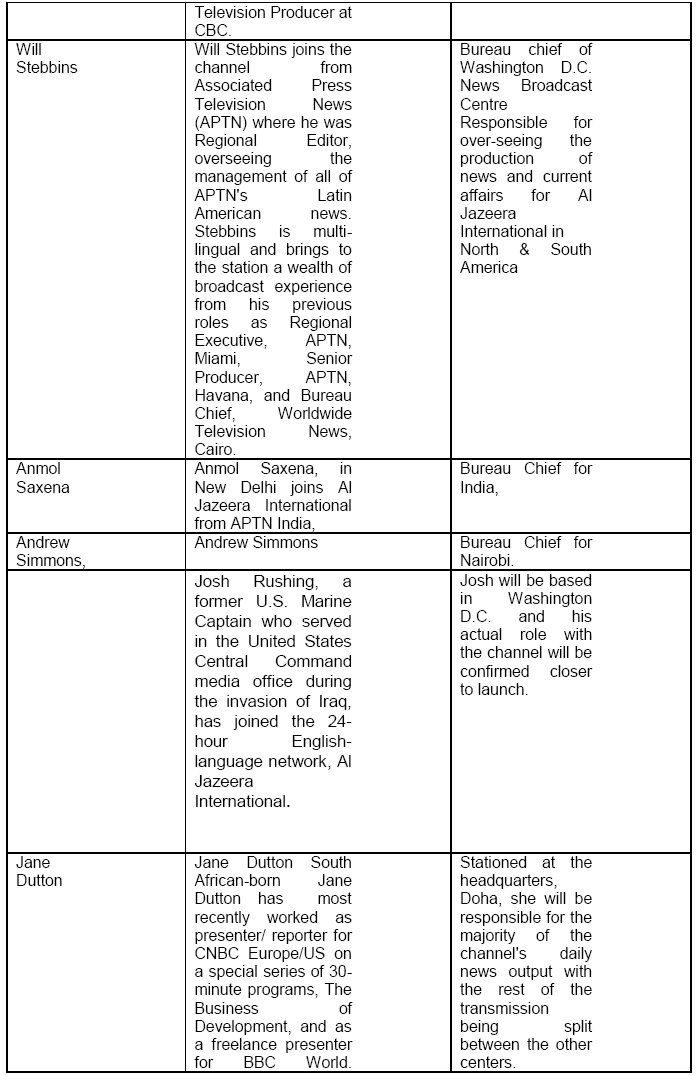

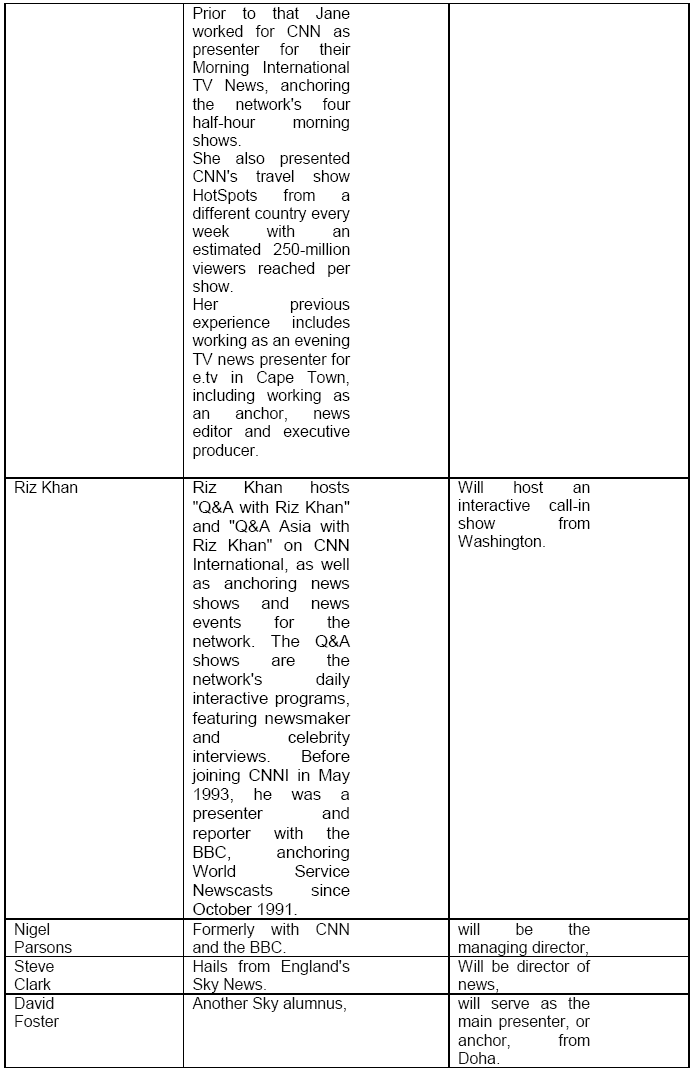

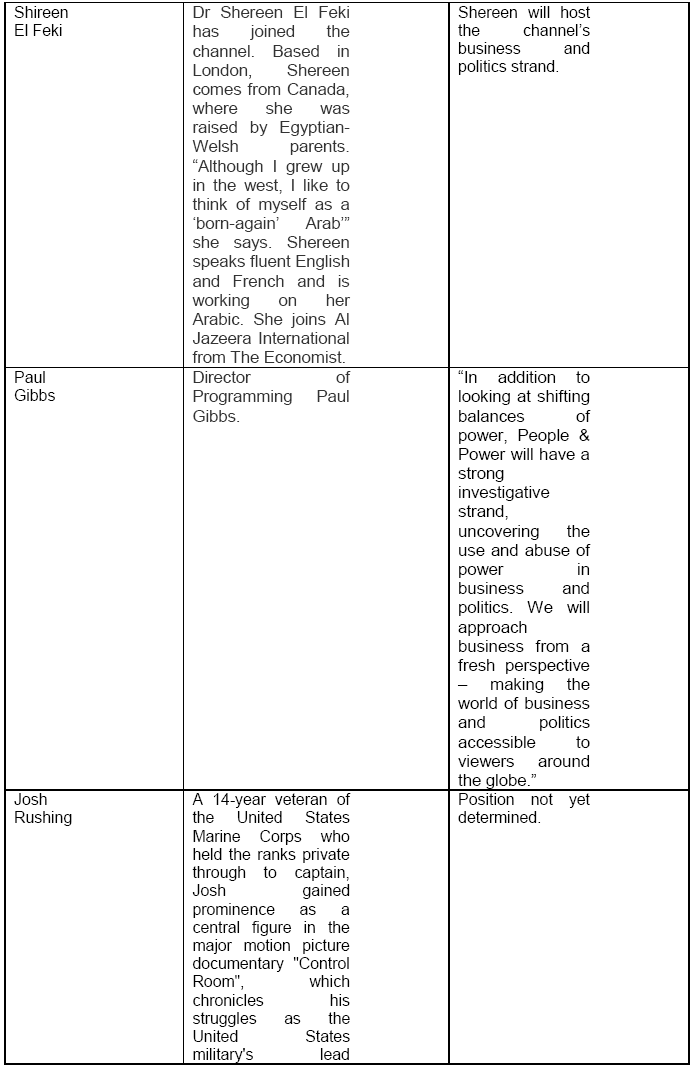

Building on the success of Arabic-language Al-Jazeera, the station decided to go global by hiring the strongest international staff it could find. Field theory suggests that Al-Jazeera did so by amassing symbolic capital by using the most exacting professional standards to hire its international staff out of the 4,000 applications it had received. Waddah Khanfar, managing director of Al-Jazeera, told a gathering at the 2nd Al Jazeera Forum held in Qatar in 2006 that diversity was going to be the channel's motto. An examination of the table below suggests that the station had achieved that goal. The staff hired in 2005 has British, Canadian, Australian, Indian, South African and American journalists, including a former American Marine (Al-Jazeera International, 2006).

Nigel Parsons, Managing Director of Al-Jazeera International said that AI-Jazeera had hand-picked its bureau chiefs, and strategically placed its news broadcast centres across the globe, to ensure that their reporting “will bring together a complete picture of world news and address the many perspectives of complex current affairs." The station promised to introduce inclusive reporting, and wants to revolutionize viewer choice by offering an alternative to traditional Western news media by providing different perspectives (Al-Jazeera International, 2006). The new staffers say that the station will be different because locals will be covering news events so that news is not presented through a foreign viewpoint (Al-Jazeera International to go on Air, 2005). In other words, no more Michael Jackson and Terry Schiavo for the Middle East and Latin America, or even Asia, and more detailed coverage of Kuwaiti and Latin American and Indian elections. Al-Jazeera also announced a new service in Urdu (the National language of Pakistan and one of the official languages of India), in advance of plans to offer similar services in French, Spanish and Turkish. The agreement the station signed with the biggest cable company in Asia will offer a 24-hour new service meant to attract about 150 million viewers, most of them in Asia, according to Hamad al-Nuaimi, marketing manager (AlJazeera English on air by spring, 2006; and Urdustan.net, 2006).

Josh Rushing, who was hired by Al-Jazeera says that he was excited to be working for a global organization “when American media has become so nationalised.” Rushing added that he “witnessed during the war how the U.S. media was co-opted by the U.S. government's messaging. I am proud to be part of a news network that believes in the power of the un-spun truth" (Josh Rushing, 2005). Director of News, Steve Clark, notes that the station’s news reporting will uphold the strictest guiding principles of accuracy, impartiality and objectivity, whilst being fearless in its reporting to earn viewer trust (Al-Jazeera International, 2006).

Al-Jazeera has also sought to include Africa in its news bureaus. Tumi Makgetla started his article on the Al-Jazeera-Africa connection by noting that, “If wars and genocides were Africa’s only news, African newspapers and international news networks like CNN would run the same stories. But Al-Jazeera International (AJI) aims to be different.” Claude Colart, the senior producer at AJI’s Johannesburg bureau, promises to bring “fresh 360 degree [change] to news coverage.” By fresh, he meant that, finally, African news will be run as part of the normal news cycle -- not just when violence occurs (Makgetla, 2005). Al-Jazeera has established an office in Zimbabwe and is one of the few stations to do so. This comes at a time when many international media organizations, including the BBC, have had their correspondents expelled from Zimbabwe (BBC, January, 2006). Says Pepe Escobar:

The writing on the (global) wall is now inevitable: region-to-region economic deals, more exports, and increased distancing from the weak dollar. In this renewed South-South cooperation, trade and commerce prevail over invasion and regime change; respect to UN resolutions regarding military occupations prevail over alienated terrorism rhetoric. There's an alternative global agenda in town (Escobar, 2005).

As Bourdieu notes, cultural capital encompasses such things as educational credentials and technical expertise (Bourdieu, 2005, p. 55). It used to be that Western nations were the ones who had the technical expertise in television, and many directors and technicians from Africa and Asia went to the BBC for training. The BBC is no longer the only place for training, and Al-Jazeera has a training center that caters to Arabs and others and conducts the training in English. Al-Jazeera hires trainers and has become the center for ambitious people who want to train (Robinson 2005).

Field theory suggests that journalism has its own “nomos,” and

that its members seek to maximize their cultural resources. The type of news Al-Jazeera broadcast, such as interviews with Osama Bin Laden, were obtained in the spirit of the scoop and to fulfill its mandate to cover both sides of the story as its logo suggests (“The Opinion and the other opinion”), according to the station. Field theory also suggests that even though international broadcasters come from different regions, they all aspire to compete in providing the best news possible, or the best intellectual capital.

The BBC, who up to the 1980s was the most respected of news sources, has lost its place to regional networks, especially to Al-Jazeera. The BBC has regretted getting out of the Arabic news when it closed BBC Arabic it ran with Saudi Arabia (17 of whose staff joined Al-Jazeera). The BBC plans to launch BBC Arabic Television in 2007. The venture, which will cost $32.9 million a year to run, will offer the only tri-media - television, radio and online - service in the region. The BBC is hiring staff it had lost in the past to Al-Jazeera Arabic. The news editor for the BBC World Service's new Arabic-language television station will be a former employee of its main competitor,

Al-Jazeera, Salah Negm. Ironically, when Al-Arabiyya was founded in 2003, it hired away several Al-Jazeera staffers, including Negm, a former BBC program editor who said, "I don't underestimate the challenge - or the competition in a crowded media marketplace" (BBC Arabic Television, 2006).

The reaction of the United States government to the new forms of media ranged from an initial boycott, to allowing high-level employees to engage with it, to the establishment of Al-Hurra (The free one) TV, and the funding of a number of stations in Iraq (Sharp, 2003). The U.S. government is also aggressively spreading its message through its Public Diplomacy staff at the State Department (Karen Hughes, 2005). The U.S. is targeting Syria and Iran with its specially prepared broadcasts and planning to start targeting Arabs in Europe (Survey finds Alhurra, 2006; US to expand Persian-Language, 2006; US to start Arabic Language Broadcasts to Europe, 2005). The main problem with this formulae is that those American efforts are government-driven, and so, viewed as illegitimate because they fall in the political, rather than in the journalistic field. On the other hand, those American and British and other journalists who care about in-depth international news are joining Al-Jazeera English.

African and Latin American officials are promising not to interfere in the content of Al-Jazeera International or in TeleSur precisely because they know that being perceived as part of the political field will delegitimize the journalistic field enterprise. Cultural capital has to come from independent sources, even if funded by the government. Al Jazeera staffers insist that they are not competing with Middle Eastern satellite station, “Our real competition is the global broadcasters,” says one staffer (Sheikh, 2004, p. 3).

The French are also in the race. TV channel France 24, launched in December 2006 in English and French, added Arabic in April 2007. The station is counting on viewers who have become increasingly "skeptical of the world vision offered by the Anglo-Saxons like BBC World and CNN International," and "are looking for contradictory opinions — which is what France 24 is proposing by relying on French values." Although the project was the brainchild of French President Chirac in 2002, it was pushed forward because he was angered by the way CNN and the BBC presented France's opposition to the Iraq war. “Station executives say the aim is to offer an alternative voice in a world television news market dominated by the "Anglo-Saxon" giants as well as the Qatar-based Al-Jazeera, which last month opened a service in English.” The station will be broadcasting to a potential Arab audience of 20 million. Interestingly, the web site of the station notes that it has a staff in which 28 nationalities are represented. It adds that “employees have come from more than 24 different televisions including CNN, BBC, [and] Al Jazeera” (France 24, 2007; AFP, October 31, 2006; AFP April 2, 2007).

The visibility and reach of TV makes it central to all political action. Patrick Champaign suggests that “the functional weight of the audiovisual sector in the total process of news production tends to be greater and greater” or is at least shared with newspapers” (2005, p. 60). In the journalistic field, there is competition for legitimate appropriation of what is at stake in the struggle in the field (Bourdieu, 2005, p. 44). The media are important because they have the “power of consecration- the power to say who and what is important, and what we should think about important things and people” (Champaign 2005, p. 58). A Bin Laden that no one interviews is relegated to oblivion; thus the U.S. government’s anger at Al-Jazeera to the point of joking that it wants to bomb the station, and as some, including Al-Jazeera claim, has already bombed it twice in Afghanistan and Iraq. The United States government denies those charges, but does not view the Bin Laden tape in journalistic terms as the scoop Al-Jazeera thinks it is.

Al-Jazeera and TeleSUR have constructed their identity globally as champions of Arabism and the Latin American masses. They have constructed their global journalistic identity relationally as one that does not share the values of infotainment that are gaining ground in the U.S.A.

The power of journalists is not individual, but collective; power they have collectively accumulated in the course of history (Champaign, 2005, p. 58). Thus, there is a limit to what the United States can do to stop Al-Jazeera from broadcasting different Arab viewpoints as it sees fit. As Al-Jazeera moves into the Indian, Pakistani and Chinese markets, its power will be felt everywhere. But as the BBC and French TV operate in Arabic, the competition for defining Middle East and world events will be fierce. AND IT’S ALL GOOD. The days of one-way global communication; free flow to the East, but no flow to the West, are also SO OVER.

There is a great deal of ferment in the global field with different countries and governments entering the news business. This analysis illustrated how the positions of different journalistic fields, old and new media, have changed. Stations that used to enjoy world dominance are now in a crowded field. Changes in news coverage of any issue are the result of internal transformations of the journalistic field and transformations external to that field (Marchetti, 2005). In the internal transformations within journalism, the world no longer depends solely on AFP, AP, UPI, TASS and Reuters. News may often travel from West to East or from North to South, but not without being challenged by news sent from South to South and from East to East. There was a time when everyone trained at the BBC. Today, the BBC and Al-Jazeera and French TV poach each other’s producers and anchors. It is interesting, then, that those who now seek to “impose the legitimate vision of the social world” are in a class of their own and are almost interchangeable. The external changes in the field involve the demise of the British Empire, and with it, the ability to determine what is news. The failure of the neo-cons to remake the Middle East in their own image in six days and to rest on the seventh day, put strains on the credibility of the United States government as a credible communicator. Those external factors opened the door to Al-Jazeera English and to TeleSUR.

This study has also commented on the newly acquired clout of Al-Jazeera in the global system, and on the ambitions of TeleSUR to do for Latin integration what Al-Jazeera has done for Arab Nationalism. The study has assessed the cultural capital both stations have amassed through their reach and their hiring practices. Al-Jazeera’s professional approach to hiring and the diversity of the voices it allows to be heard add to its credibility, If not with the Untied States government. Al-Jazeera is literally the station that flew over the cuckoo’s nest. The station has already had a great impact regionally, and has spawned a number of imitators. Whether or not Al-Jazeera will make it into the American market will not make too much of a difference because its global reach will be tremendous even without the American audience. As for TeleSur, it is too early to assess where it is going because it started only in 2005, but the ideas that animate it promise to hasten the integration Latin America.

Copyright © 2025 Global Media Journal, All Rights Reserved