ISSN: 1550-7521

ISSN: 1550-7521

Olga Baysha

University of Colorado, Boulder USA

Visit for more related articles at Global Media Journal

It has been argued that transnational communication technologies lead to the formation of a global public sphere (Volkmer, 2003). Using a framing analysis, this article examines whether signs of global public deliberation are present in U.S. and Ukrainian media coverage of the Russia-Georgia military conflict of 2008. Several popular national dailies and weeklies are analyzed, as well as niche periodicals of diverse political orientations. The study shows that U.S. media predominantly blame Russia; Ukrainian periodicals distribute responsibility among Russia, Georgia, and the United States. Pro-Russian views, popular in Ukraine, are ignored by U.S. news outlets. The exclusion of pro-Russian views from U.S. public discourse leads not to mutual understanding, but to animosity on the part of pro-Russian Ukrainian media toward the United States.

Media, framing, globalization, deliberation, public sphere

The idea of a of a Global Public Sphere

One of the most controversial paradigms of international communication studies is the idea of the “global public sphere.” Scholars who favor this outlook argue that new transnational media technologies, which create opportunities for global multicultural dialogue, lead to the formation of a global public sphere (e.g. Volkmer, 2003). This belief, popular among communication scholars, is in conflict, however, with the perspective of political theorists who claim that the public sphere is not about intensified communication per se; it is a “fundamental concept of a theory of democracy whose attempt is normative” (Habermas, 1992, p. 446). According to the classical definition by Habermas (1964/1974) -- one of the most prominent theorists of deliberative democracy -- the public sphere is a realm of social life where the energy of public opinion is generated to be consequently transformed into an effective political force able to keep state bureaucracies accountable to their citizens. To reach its full potential, the public sphere has to possess two basic characteristics: the discussion of public matters should be rational, and all citizens should have free access to it. Mass media should be accessible to the general public and contain rational discussions of legitimate public concerns (Habermas, 1962/1989).

Among political theorists of democracy, the idea of the global media environment as a public sphere has evoked plenty of skepticism. The following critical questions have been put forward: how can the controversies within transnational discursive areas be translated into a political action, if they are not legitimately related to any sovereign state? If those who participate in public discussions are not fellow citizens holding equal social status, how can their opinions be legitimately transformed into an effective political force? Is it possible to come to any kind of agreement if those who seek it don’t share any common political culture? (Beck, 2003; Fraser, 2007; Habermas, 2001).

Contemplating the conditions for the emergence of the global public sphere, theorists of democracy stress the importance of common political culture as its indispensable prerequisite. According to Garnham (1992), for example, a global public sphere should be characterized by the “duty to listen to the views of others and to alternative versions of events” (p. 368). Bohman (1997) claims that international peace can be achieved only by means of such a cosmopolitan public sphere, in which opinions are “multi-dimensional” and “many-sided” (p. 185). Beck (2003) argues that the whole meaning of learning in the globalization age should be reoriented toward “understanding of other cultures,” “dialogical attentiveness,” and “integrative thinking” (p. 138). Such attention to other peoples’ opinions, according to these and numerous other thinkers, would pave the way to formation of a global political culture and, based on it, new cosmopolitan publics or even citizens of a world state.

While debating “how responsible globalization can be politically molded and achieved” (Beck, 2003, p. 129), the theorists cited above all contemplate future democratic transformations of global scale. Other scholars, on the contrary, argue that these positive changes have already come into play. Volkmer (2003), for example, claims that “in western, democratic societies, whose political systems believe in ‘freedom of expression,’ the global content discourse provides an additional information source… and refines political reasoning ‘rationality’ within the national public sphere” (p. 15). According to this model, transnational political reasoning can be achieved through national media networks incorporated into a global communication system. The model implies that, unlike ordinary citizens, journalists and editors have more resources to get access to diverse multicultural information provided by globally interconnected information networks. Ideally, media writers would incorporate these multifarious perspectives into their materials. In such a way, a mediated exchange of arguments and a global rational discourse would be established.

Suggesting that global deliberation can be achieved through interconnected global networks, Volkmer (2003), however, provides little empirical evidence to ground her propositions. This study has been designed to empirically test her mediated model of the global public sphere by examining whether signs of global public deliberation are present in U.S. and Ukrainian media coverage of the Russia-Georgia military conflict of 2008.

The Context

The military conflict between Russia and Georgia broke out on August 8th, 2008, after Georgia launched an aerial bombardment and ground attack on South Ossetia, a self-proclaimed republic striving for independence. The same day, Russian troops were deployed first in South Ossetia, and then in undisputed territories of the Georgian state. On August 13th, Russia and Georgia agreed on a cease-fire, according to which their militaries were to pull back to the positions they occupied before the violence erupted.

Georgia and South Ossetia have a long history of struggle. In the aftermath of the Russian Revolution of 1917, South Ossetians incited a series of rebellions against Georgia, “resulting in 5,000 Ossetians dead in fighting and reprisals and another 20,000 taking refuge” (Kaufman, 2001, p. 88). In the late 1980s, another conflict resulted in civil war, in which about 60,000 Ossetians took refuge in Russia (Nygren, 2008). In two referendums, in 1992 and 2006, the population of South Ossetia voted in favor of joining Russia. Neither of the plebiscites was recognized internationally. However, by the beginning of the Russia-Georgia military conflict, more than fifty percent of the South Ossetians already had Russian passports (Nygren, 2008).

From the beginning of the conflict, the Western media involved Ukraine into the conflict. Many of their authors claimed that Ukraine would be Russia’s next target “because “Russians tend to believe that country is their ancient patrimony” (Pryce-Jones, 2008): “The political shock waves from Moscow's invasion of Georgia are ripping through nearby Ukraine, rattling nerves that the next regional flash point may be its Crimean peninsula” (Alastair, 2008, p. 32); “Russia's aggression toward Georgia should not be viewed as an isolated incident… It is only a question of time before Moscow turns up the heat on Ukraine” (Brzezinski, 2008, p. 6); “Russia has scared its neighboring states…Now the Kiev government has unhesitatingly asked for a path to NATO membership” (Zakaria, 2008, p. 63), and so forth.

The popularity of the belief that Russia is ready to conquer Ukraine because Moscow considers Ukraine its “ancient patrimony” requires historical explanation. Ethnically, Russians and Ukrainians are very close: originally, both nations belong to Eastern Slavs; Kievan Rus, an ancient Eurasian state, was a forebear for both nations. It was the Mongolian invasion in the 13th century that separated the Russian and Ukrainian histories: “Russia remained under Mongol rule for another 150 years, whereas Ukraine gradually became part of the Polish- Lithuania medieval state” (Bukkvoll, 1997, p. 61). In the 17th century, the historical paths of Ukrainians and Russians converged again. From 1654 until the end of the 20th century, the major parts of southeastern Ukrainian territories were under Moscow’s jurisdiction; western Ukraine was predominantly under Polish rule. Total reunification of Ukraine was accomplished in 1939-1940. Centuries of living under different civilizations had left the mark, however: mainly, western Ukrainians speak Ukrainian and attend the Catholic or Uniate Church, whereas southeastern Ukrainians speak Russian and attend the Russian Orthodox Church (Kovalova, 2007).

Given the intricate nature of the international relations within the territory of the former USSR, two broad questions arise: Was there any reason for U.S. writers to call for Ukraine’s defense from Russia by means of NATO membership (e.g., Pryce-Jones, 2008)? To what extent does the U.S. image of Ukraine in relation to Russia in general and the Russia-Georgia conflict in particular correlate to Ukraine’s image of itself? To answer these questions, the study has employed framing analysis.

With little personal experience in politics, people depend on news media to understand the political world. This provides media with the power to frame reality for the public. Researchers argue that “how people think about an issue, especially a political issue that is inherently ambiguous, is dependent on how the issue is framed by the media” (Semetko & Valkenburg, 2000, p. 94). Gamson and Modigliani (1987) defined a media frame as “a central organizing idea or story line that provides meaning to an upholding strip of events…. The frame suggests what the controversy is about, the essence of the issue” (p. 143). According to Entman (1993), to frame means “to select some aspects of a perceived reality to make them more salient, thus promoting a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation” (p. 52). In communication flows, frames manifest themselves by means of framing and reasoning devices. Framing devices (metaphors, catchphrases, exemplars, depictions, and visual images) suggest a framework within which to view the issue, while reasoning devices (roots, consequences, and appeal to principle) provide justification or reasons for general positions (Gamson & Lasch, 1983, p. 399).

Researchers argue that frames can be located in several points of the communication process: in the minds of media makers and the audience, in media content, and in culture (Entman, 1993; Scheufele, 1999). Because frames are related to culture, their use looks so natural that the process of social construction remains invisible and can be regarded as a mechanism of reproducing political status quo (Lewis, 1999). As Gorp (2007) argues, “the notion of a cultural stock of frames more easily leads to the idea that there are more frames than those that are currently applied” (p. 63). Alternatives to the existing frames can lead to different problem definitions, causal interpretations, moral evaluations, and treatment recommendations. It follows that critical media analysis needs to distinguish the currently applied frames from their alternatives in order to be able to explain their persistence.

The framing theory, which was originally elaborated in the field of cognitive psychology, has been widely adopted in recent years not only in communication studies but also in other disciplines: sociology, economics, linguistics, public-relation, and so forth. It is this diversity of approaches to framing research and different meanings of the word ‘‘frame’’ adopted within these approaches, that ultimately brought to theoretical vagueness and “the absence of an unequivocal conceptualization” (Gorp. 2007, p. 60). To avoid misunderstandings, this paper will stick to Gamson and Modigliani’s (1987) conception of “frame” as “a central organizing idea or story line” (p. 143) that provides meaning to phenomena or events. It will also follow Entman’s elaboration (1993), according to which this “story line” should promote particular problem definitions, causal interpretations, moral evaluations, and treatment recommendations.

This study focuses on three research questions in regard to the Russia-Georgia crisis:

R1. What are the most popular frames that different U.S. media employ in covering the crisis?

R2: What are the most popular frames that different Ukrainian media employ in covering the crisis?

R3: Are there any consistent differences in the use of media frames by U.S. and Ukrainian media outlets?

If the mediated global public sphere envisaged by Volkmer (2003) indeed exists, it would mean that, as applied to the issue under our analysis, popular arguments on the Russia- Georgia conflict presented in the Ukrainian public sphere would be also contemplated in U.S. mediated discourse, because the geopolitical interests of both countries are potentially affected by the outcome of the crisis (Friedman, 2008).

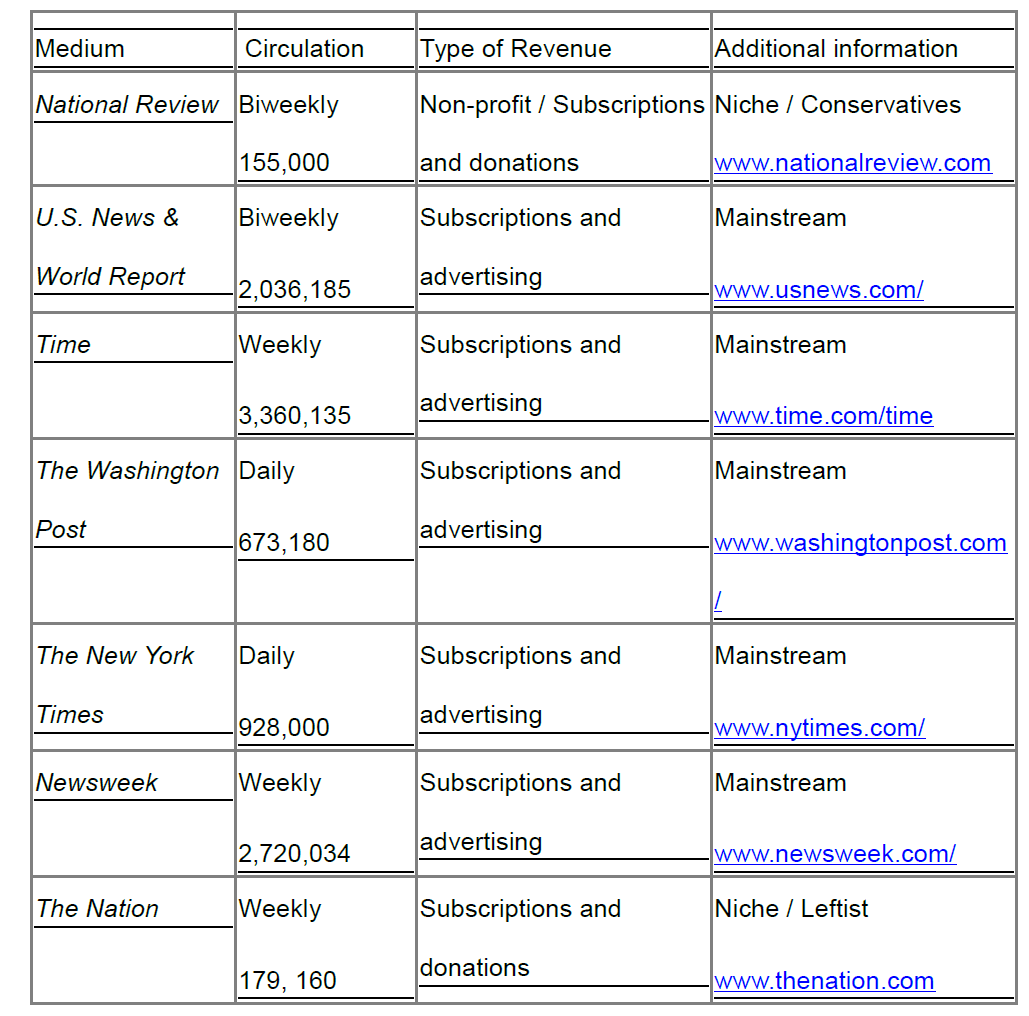

To investigate the research questions, the author analyzed the content of Ukrainian and U.S. popular print media. To embrace the range of ideas presented in the U.S. public sphere, the popular national dailies The New York Times and The Washington Post, as well as the traditional weeklies Time, U.S. News and World Report and Newsweek, were selected for analysis. To check for less mainstream views, the conservative National Review and the leftist Nation were included in this analysis as well.

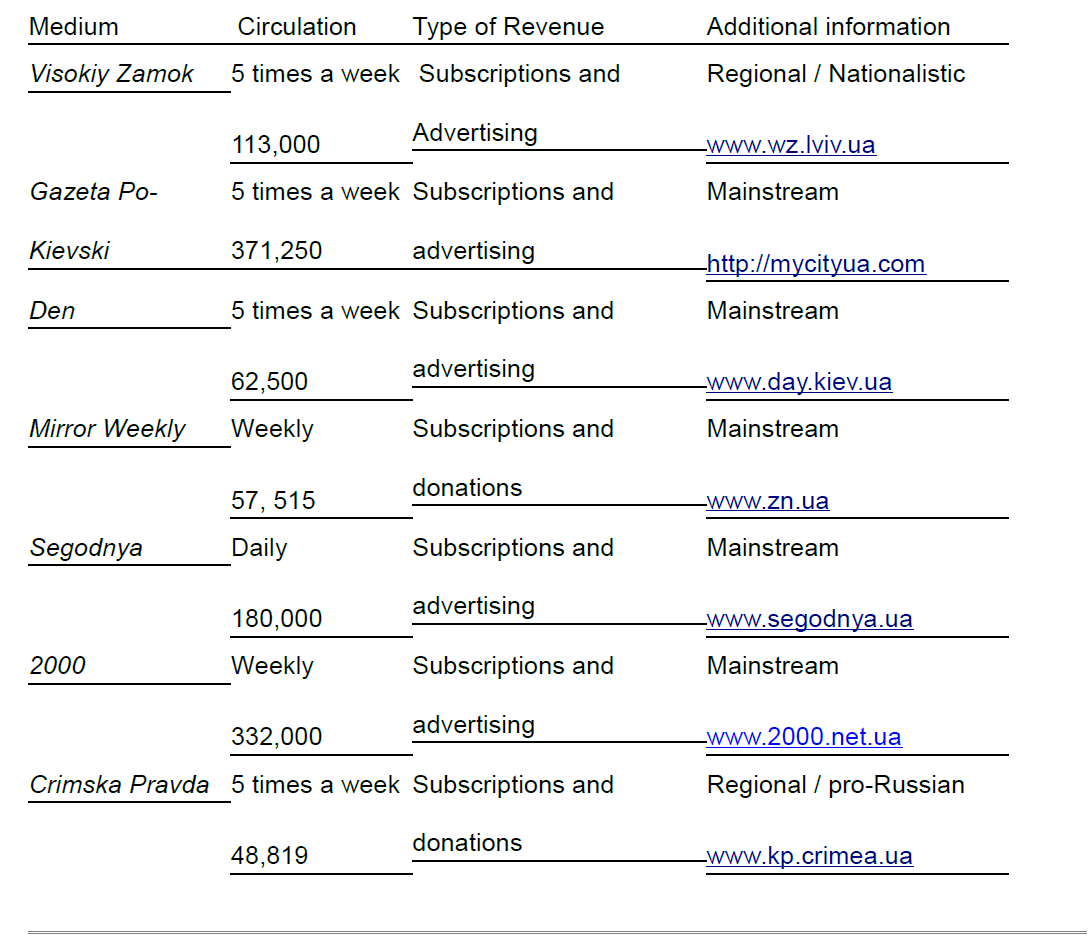

The Ukrainian public sphere was represented by the traditional national dailies Segodnya, Gazeta po-Kievski and Den, as well as by the popular weeklies Mirror Weekly and 2000. To include views that are more extreme, regional newspapers of diametrically opposed political orientations were also analyzed: Crimska Pravda (Crimea, Southern Ukraine; represents the views of pro-Russian publics) and Visokiy Zamok (Galicia, Western Ukraine; represents the views of Ukrainian nationalists).

None of the selected news outlets – both U.S. and Ukrainian – was an official mouthpiece of government politics (basic information of the media is presented in Appendixes A and B). Only editorials and stories containing opinions and commentaries were investigated. No hard or brief news items were included because the particular importance of commentaries in the process of public opinion formation (Habermas, 1964/1974, p. 53) and because editorials have been shown to be generally representative of newspapers’ specific framing of issues (Nacos, 1990).

The coverage under analysis was limited to three months of the crisis aftermath, from August 8, the day the crisis began, until November 4, the day of the U.S. presidential elections – an event that marked the potential beginning of a new stage of U.S.- Russian mediated dialogue. No sampling was involved. All the articles related to the crisis within the abovementioned window of coverage were analyzed qualitatively. Mechanical reckoning of the key words was avoided in order not to lose sight of more subtle cultural nuances regarding how the crisis was depicted and explained by different U.S. and Ukrainian news outlets. Commentaries of U.S. media were taken from the Proquest database. Articles from Ukrainian periodicals were picked up from their Internet versions. The unit of framing analysis was the article. Each of them was coded based on the country, media outlet, frame, and date. The results were analyzed using cross-tabs calculations; the significance of differences was established with the help of Chi-Square test.

All the Ukrainian articles were published in either Ukrainian (Visokiy Zamok, MirrorWeekly, and Den ) or Russian (2000, Segodnya, and Crimska Pravda). The results reported here have been translated into English accurately and precisely because the author is a native Ukrainian-Russian speaker.

In total, 303 commentary stories related to the Russia-Georgia military crisis were analyzed. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the data.

Research Question 1 asks what are the most popular frames that U.S. media employed in covering the crisis.

Analysis of the articles published in U.S. news magazines reveals four main ideas or “story lines,” in accordance with which the Russia-Georgia conflict is reported and explained. For the convenience of further discussion, these media frames have been conditionally assigned the following names: (1) “Russia is an aggressive empire,” (2) “Russia is a difficult but valuable partner,” (3) “Washington carries out fallacious foreign policy,” and (4) “Georgia miscalculated Russia’s response.” The results are presented in Table 3.

“Russia is an aggressive empire.” In brief, this media frame can be retold in the following way: After years of economic decline following the demise of the Soviet Union, Russia is restoring its might along with its traditional imperial aggressiveness toward independent neighbors. Russia doesn’t tolerate democracy and freedom on its borders; therefore, pro-Western Ukraine might easily become its next target. To resist this totalitarian assault, the civilized world should shun Russia and defend the fledgling democracies of Georgia and Ukraine by accepting them into NATO. Here are some examples of the typical claims of this story line: “Restoration of the old Russian Empire, where surrounding countries are either vassals or clients (Walsh, 2008a, p. 16); “Moscow's ruthless attempt to suborn, subdue and subordinate (Brzezinski, 2008, p. 26); or “The bear is back on the prowl (Walt, 2008, p. 28). As Table 3 shows, among periodicals, conservative National Review employs this media frame in the highest percentage of its stories. Leftist The Nation uses it least often.

“Russia is a difficult but valuable partner.” This media frame can be summed up as follows: Although Russian actions against Georgia are unacceptable, cooperation with strong, wealthy and increasingly influential Moscow is vitally important for U.S. global interests. That is why Russia, instead of being excluded from the global community of democratic countries, should be incorporated into it even more. Here are some examples of the basic claims of this version of the Russia-Georgia story: “To deal effectively with challenges such as terrorism, proliferation, energy security, and Iran and North Korea, Russia is part of that equation” (Walsh, 2008b, p. 14); “What Richard Nixon said 40 years ago about China – that ‘…we simply cannot afford to leave China forever outside the family of nations, there to nurture its fantasies, cherish its hates and threaten its neighbors’ – applies equally now to Russia” (Haass, 2008, p. 9). As Table 3 shows, Newsweek is most likely to exploit the idea of cooperation; National Review totally ignores it.

“Washington carries out fallacious foreign policy.” In this version of the story, the USA is assessed partial responsibility for the Caucasian conflict from two different perspectives: (1) The conflict probably would not have happened if the United States had provided Georgia with more support, taking into account that Georgia is a devoted U.S. partner; and (2) The tension between Russia and Georgia is a logical outcome of provocative U.S. foreign policy in the former USSR region. The different perspectives imply different solutions: either supporting Georgia by means of NATO or revising foreign policy tactics. Here are some examples of typical claims of this media frame: “2,000 Georgian soldiers made up the third biggest coalition force in Iraq… The main airport road in Tbilisi is named George W. Bush Street” (Walt, 2008, p. 28); or “The Bush administration unnecessarily antagonized Russia by expanding NATO and withdrawing from the anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty” (Cockburn, 2008, p. 11). As Table 3 demonstrates, for the most part, the theme of Washington’s responsibility for the conflict is used by the New York Times. Conservative National Review and conservative-leaning U.S. News and World Report do not employ it in their stories.

“Georgia has miscalculated Russia’s response.” This story pins sole responsibility for the conflict on Georgia’s president, Mikhail Saakashvili. The main argument fits into one sentence: he has dared to send troops into South Ossetia without properly estimating U.S. support and Russian response. Here are some examples of the typical claims made within this story line: “Georgian President Mikhail Saakashvili's… underestimated the Russian response, and he overestimated what the United States and others would do on his behalf" (Haass, 2008, p. 9); or "It was John McCain's pal Michael Saakashvili who set the ball rolling…The Georgian President Michael Saakashvili sent forces into South Ossetia in violation of an earlier agreement” (Cockburn, 2008, p. 6). This view is employed most conspicuously by the leftist The Nation, while National Review, Time, and U.S. News and World Report never once incorporate it into their stories.

Research Question 2 asks what are the most popular frames that Ukrainian media employed in covering the crisis.

Qualitative analysis of media stories related to the Russia-Georgia military conflict published by Ukrainian media reveals six main story lines according to which the conflict is reported and explained: “Russia is an aggressive empire,” “Washington seeks world dominance,” “Georgia commits genocide against Ossetians,” “Russia is a difficult but valuable partner,” “Western media wage information wars against Russia,” and “West exercises double standards.” and Table 4 represents the findings.

“Russia is an aggressive empire.” In many ways, this media frame resembles the perspective of U.S. periodicals: Russia yearns to revive its super-imperial might; it doesn't tolerate democracy and freedom; it understands only the arguments of force. Here are some examples of typical claims of the frame’s Ukrainian version: “Russian policy is the policy of bayonet, multiplied by the ‘gas diplomacy’” (Rakhmanin, 2008a); “Russia demonstrates a morbid desire to become a super-state” (Balyuk, 2008); or “The aim was not only to humiliate Georgia and its ‘impudent’ president, but also the whole West, and especially the USA” (Timots, 2008). As Table 4 demonstrates, there is a distinct split of the Ukrainian public sphere with reference to this frame: While western Visokiy Zamok employs it in 61.8% of its articles, southern Crimska Pravda and pro-Russian 2000 do not use it at all

“Washington seeks world dominance.” This media frame assesses U.S. responsibility for the Caucasian conflict, much like the frame “Washington carries out fallacious foreign policy” employed by U.S. periodicals. But, unlike U.S. media, Ukrainian outlets focus not on tactical issues of U.S. foreign policy but on its strategic line. Basically, they claim that by all possible means, the USA strives to keep its global domination. Rising Russia interferes with these plans, so it should be weakened by establishing and supporting puppet pro-U.S. regimes on Russian borders. Here are some examples: “The military defeat of Georgia became a sonorous slap in the U.S. face with its plans to surround Russia with a sanitary

cordon” (Buryak, 2008); “Yushenko’s and Saakashvili’s regimes have the same puppeteer” (Verbitskaya, 2008); or “The long ears of the American donkey stick out of all the anti-Russian Georgian tricks” (Buryak, 2008). As Table 4 shows, the distribution of this frame in Ukrainian media shows that territorial (cultural) and ideological factors play a decisive role again: Most actively, the theme of U.S. responsibility for the conflict is exploited by the southern Crimska Pravda.

“Georgia commits genocide against Ossetians.” Like the theme “Georgia miscalculated Russia’s response” employed by U.S. periodicals, this media frame places guilt squarely upon the shoulders of Georgian president Michael Saakashvili. However, the difference in perspectives is radical. While the U.S. “Georgian Imprudence” story is basically about Saakashvili’s rashness, its Ukrainian analogue overtly accuses him of a politics of genocide towards the Ossetian people. Here are examples of some typical claims: “Georgian missile volleys destroy everything and leave no one alive in the target zone. Such a way to restore constitutional order is unacceptable” (Silina, 2008); “The fascist actions of Saakashvili and American hirelings are being taken against peaceful citizens” (Grach, 2008); or “Georgian Fuhrer Saakashvili is similar to Hitler, who also cried out about his ‘striving for peace’ before waging war” (Lozunko, 2008). The distribution of this frame in Ukrainian media differs from previous cases: the claim of Georgian guilt is supported not only by the pro-Russian Crimska Pravda, 2000, and Segodya but also by the pro-Western Mirror Weekly and Gazeta Po- Kievski.

“Russia is a difficult but valuable partner.” Like its U.S. analogue, the Ukrainian frame also stresses the idea of partnership with Russia. However, there is a noticeable difference in how it is constructed in U.S. and Ukrainian versions. While U.S. media basically concentrate on Russia’s importance for the United States’s geopolitics, Ukrainian periodicals tend to focus on global security as a whole. They often tend not to take anybody’s side, warning against dangerous political games and calling for unity and cooperation in the face of real challenges: terrorism, poverty, illnesses, and climate change. Here are some typical examples: “It’s important to refrain from black-and-white judgments, because the situation is very complicated and the terms ‘aggressor’ and ‘victim of aggression’ don’t apply here (Silina, 2008); or “There are other global processes in the world... Let’s hope that when fighting against these threats, both Russia and Georgia will be on one side” (Silina, 2008). As Table 4 shows, this perspective has become dominant in Ukrainian coverage of Russia-Georgian conflict.

“Western media wage information wars against Russia.” This is the first among two media frames that appear to be endemic to the Ukrainian public sphere – they have no analogue in U.S. media. The story conveyed in this frame is about a supposed information war that Western media wage against Russia. Here are some typical claims: “For almost the whole day they [Western media] did not notice punitive action by Georgia against South Ossetia but, as if under command from a control center, they got into gear only after Russian columns moved to prevent genocide” (Lozunko, 2008); or “U.S. media bring back to life Russia’s image as an enemy, which is important since the mythology of the ‘fight against global terrorism’ has exhausted itself” (Darenskiy, 2008). As Table 4 demonstrates, Crimska Pravda is most likely to exploit this frame.

“West exercises double standards.” Similar to the previous one, this frame appears only in the Ukrainian information space. It doesn’t accuse any one country in particular, but the whole Western world. The name assigned to the frame illustrates its main idea: Russia would not dare to behave so boldly but for the Western duplicity in respect to issues such as energy policy, the Chechen war, and Kosovo’s independence. Here are some typical examples of the frame’s claims: “Wasn’t it known that the precedent of Kosovo was directly projected on the South Ossetia, Abkhazia, and more than 150 other frozen conflicts?” (Silina, 2008); or “The decision to recognize the Albanian drug dealers’ den [Kosovo] as an independent state was a total idiotism. However, the West did it, unchaining the Russian bear [as revenge]” (Yeryomin, 2008). As Table 4 shows, the division of the Ukrainian public sphere into two distinct parts on the basis of cultural and ideological differences is not so radical in this case: both southern Crimska Pravda and western Visokiy Zamok equally support the claim.

Research Question 3 asks whether there are any differences in media-frame employment between U.S. and Ukrainian weekly news outlets.

As Table 4 shows, contrary to the conception (popular in the USA) of a united, democratic, pro-Western Ukraine scared of aggressive Russia, the Ukrainian public sphere is culturally and ideologically split into two distinct parts: “pro-Western” and “pro-Eastern.” This is reflected in how different media frame the Russia-Georgian crisis: pro-Western public opinion, expressed by the Visokiy Zamok, Gazeta Po-Kievsky, and Den, tends to lay responsibility on Russian imperial ambitions; the pro-Eastern view, represented by the Crimska Pravda, 2000 and Segodnya, confidently places the blame on Georgian nationalism supported by the United States’ hegemonic ambitions. The U.S. public sphere is not so deeply divided on the issue. The confidence in Russian guilt expressed by conservative National Review is shared, to varying degrees, by the popular media (U.S. News and World Report, Time, Newsweek) as well as by leftist The Nation.

There is also a difference in how U.S. and pro-Western Ukrainian media construct the frame “Russia is an aggressive empire”: in its U.S. version, the theme of “scared Ukraine” and the necessity of its defense by means of NATO is a popular one (37 percent of the articles which employ the frame “Russia is an aggressive empire” examine this idea); in its Ukrainian analogue, only two percent of the whole number of articles appeal to NATO. The reasons for such difference will be discussed below.

The study has revealed an interesting difference in the way Ukrainian and U.S. media contemplate the United States’ responsibility for the crisis: While U.S. periodicals tend to stress tactical mistakes in U.S. foreign policy, Ukrainian pro-Russian newspapers accuse the United States of working to maintain global dominance and install puppet regimes on Russian borders. This perspective is not present in U.S. media. Several commentaries touch upon the “provocative” nature of U.S. policy towards Russia (expanding NATO and withdrawing from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty). However, they do not explore the topic of “puppet” and “marionette” regimes, which is popular in the pro-Russian segment of the Ukrainian public discourse.

The study has revealed the same difference in highlighting of key points within the story of Georgian responsibility in its U.S. and Ukrainian versions. While U.S. media tend to stress Saakashvili’s rashness and inability to foresee the consequences of his actions, Ukrainian periodicals accentuate the inhumanity of Georgia’s “politics of genocide” toward the Ossetian people. Given the long history of Georgian-Ossetian tense relations, it is a surprise to discover that U.S. media ignore the theme, while even Ukrainian Mirror Weekly, which obviously does not share pro-Russian views on the conflict, acknowledges that Georgian military methods of “restoring constitutional order” are unacceptable. Taking this finding into account, it is no wonder that the story about Western media that wage information wars against Russia are popular among pro-Russian writers.

Taken together, U.S. and Ukrainian media present quite different pictures of the conflict. While U.S. periodicals predominantly depict Russia to be the only villain, Ukrainian news outlets (depending on their cultural orientation) distribute blame between Russia, Georgia, the United States, and the entire Western world.

The difference in Ukrainian and U.S. views on the Russia-Georgia conflict is impressive with regard to the image of “pro-Western” Ukraine created by U.S. media. As the results of the analysis demonstrate, Ukraine is sharply divided on the issue. Such a gap in attitudes reflects the “divided identity” (Kovalova, 2007) of the country, exposed by numerous investigations. The most recent of them, conducted in the aftermath of the Russia-Georgia crisis, confirms that this gap has not narrowed: Russia is called an aggressor by 72.9 percent of respondents in the west of Ukraine, while 73.2 percent of respondents in the Crimea call Russia’s military actions in Georgia ‘a peacekeeping operation’ (Rakhmanin, 2008b).

Even more striking against the background of a “pro-Western” image of Ukraine in U.S. media are the poll figures reflecting the attitude of Ukrainians toward NATO membership. Only 18.2 percent of respondents want Ukraine to become a NATO ally, while 51.4 percent of them say they are ‘strongly against’ NATO membership (Rakhmanin, 2008b).

Talking about the “pro-Western” orientation of Ukraine as well as the necessity to defend it by means of NATO, U.S. media not only ignore a significant part of Ukrainian public opinion, but also misinform their own readers, creating a picture that does not correspond to the real world. The formation of the idea that “Western media wage information wars against Russia” in the Ukrainian information space is a direct consequence of the exclusion of the pro- Russian public opinion from U.S. media discourse. This miscommunication testifies against the proposition of Volkmer (2003) that intensified global information flows inevitably enrich the content of discourses in democratic societies. The results of this study show that the Ukrainian media discourse is more diversified in its ideas about the origins and reasons of the Russia-Georgia crisis despite the fact that the USA’s rating on press freedom is higher than that of Ukraine (Reporters Without Borders, 2008). The diversity of ideas presented in the Ukrainian media space could be better explained not in terms of democracy but from a cultural perspective: instead of being nationally unified, Ukraine falls into two distinct parts, pro-Eastern and pro-Western. Their explanations of the crisis are mutually exclusive, and there are no signs of attempts to find a common language and understand the opponents’ arguments by means of transcending initial preferences. However, Ukrainian publics at least have access to information about what their opponents think. We can hardly say the same about media consumers in the United States. Contemplating the possibility of deterring Russia by means of inclusion Ukraine into NATO, U.S. periodicals do not provide any information about what Ukrainian people think of this, thus disabling their readers from making rational judgments on the issue. On the other hand, being excluded from the discourse, pro-Russian Ukrainian publics are not able to participate in the discussion on this issue, which is of vital importance to them. This finding definitely testifies against the existence of the global public sphere. The more appropriate term would be “global information battlefield,” where intensified communication flows lead not to multicultural dialogue and mutual understanding but to even greater animosity among alienated publics.

The aim of this study is not to judge who is guiltier – Russia, Georgia, the United States, or any other party – in creating or escalating the military crisis of 2008. Neither does this study purport to identify whose version of the events – U.S. (leftist or conservative) or Ukrainian (Eastern or Western) – deserves more credence. Instead, the paper claims that substantial parts of global discourse on the Russia-Georgia military crisis are missing from the national public spheres under consideration, an absence that cannot be interpreted as an attribute of a global public discourse. Although this finding testifies against the existence of a global public sphere, the research demonstrates, however, that national media, operating in a highly interconnected contemporary world, can produce effects of a global scale. In the case of international conflicts (like the Russia-Georgia one) such an effect, as this study demonstrates, can be the “spiral of ‘anti-other rhetoric” (Le, 2006, p. 162). It is possible that in case of more peaceful issues of international co-existence the effect could be quite different. Will it be the formation of a global deliberation? More empirical research is needed to explore this question.

APPENDIX A. U.S. media

APPENDIX B. Ukrainian media

Olga Baysha is from Kiev, Ukraine. Her undergraduate degree is in Philology from Kharkov State University in Ukraine and her master’s is in Technical Communication from Colorado State University. Ms. Baysha has extensive television reporting and editing experience. She can be reached at Olga.Baysha@Colorado.Edu

Copyright © 2025 Global Media Journal, All Rights Reserved