ISSN: 1550-7521

ISSN: 1550-7521

Western Connecticut State University

Visit for more related articles at Global Media Journal

Acknowledging and incorporating ways to develop novel ideas and methods is a core skill for students. An interdisciplinary course was developed using a didactic approach that combined emerging digital technology, social media, and traditional media into an interactive learning environment to produce and disseminate live, public, regional election coverage. Questions facing the course: Can a high quality, election news program be produced despite limited resources using emerging and traditional media and successfully delivered in real time to a diverse audience? How well will students of various interdisciplinary majors work together under the stress of a high stakes project and will (their civic understanding and engagement be increased? Unsolicited feedback during and shortly after the live broadcast, student written course evaluations, live audience attendance, and student grades suggest positive results. Challenged with limited resources and facilities, within the context of a live news production class of 30 undergraduates, a technological mash-up maximized experiential learning and produced a valuable public service to a potential audience of 60,000. Studio anchors, six remote field teams, a virtual set with polling data and social media were employed. Using smartphones for cameras, Skype, digital switching equipment, and cable access television, four hours of live election coverage successfully broadcast November 6, 2012 and simultaneously aired over TV, FM radio, and the Internet. The program won two media awards.

mobility, connectivity, connectivist learning, media, politics, election coverage, technology, news, journalism, social media, web, Internet, streaming video, simulcasting, audience interactivity, video production, interdisciplinary, teaching across the curriculum, experiential learning, distribution, limited resources and funding, traditional media, emerging media, synchronous communication, participatory education

News and political information impact our lives directly and indirectly. Such information affects how we think of ourselves and those who share or disagree with our worldview, our perceptions of issues, policy, government leaders and government. We have witnessed fundamental changes taking place in our consumption of media and news. The Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism (2012) reported these changes.

In 2011, the digital revolution entered a new era. The age of mobile, in which people are connected to the web wherever they are, arrived in earnest. More than four in ten American adults now own a smartphone. One in five owns a tablet. New cars are manufactured with Internet built in. With more mobility comes deeper immersion into social networking (http://stateofthemedia-2012.org).

By 2013, Pew Research Center reported that over three cable channels, coverage of live events fell 30% from 2007 to 2012 while interview segments, which tend to take fewer resources and can be scheduled in advance, were up 31%.

This adds up to a news industry that is more undermanned and unprepared to uncover stories, dig deep into emerging ones or to question information put into its hands. And findings from our new public opinion survey released in this report reveal that the public is taking notice. Nearly one-third of the respondents (31%) have deserted a news outlet because it no longer provides the news and information they had grown accustomed to (http://stateofthemedia.org, 2013).

Whether news media have undergone a revolutionary change or are merely adapting existing practices is being debated (Alysen, 2009). But there is no debate on changes in professional practice in four areas: (a) production technologies, (b) distribution technologies, (c) economic restraints, and (d) changing audience tastes and expectations (Pew, 2012; 2013; Mitchell & Rosenstiel, 2012; Atkinson, 2013). News organizations around the world have witnessed shrinking budgets and fewer field offices (Barone & Swan, 2007). Reporters have had to do more of the production work including shooting and editing, and more of their work is in a “live” environment (Alysen, 2009). The public has become a player in agenda setting by focusing attention on issues and supplying news organizations with content through various means on websites, text messages, blogs, Twitter, emails, personal cameras and mobile phone footage.

Fourteen years ago Tickle and Keshvani presciently noted:

The discrete roles of broadcast journalist, print journalist, editor and producer, once bounded by news product specificity, task differentiation and analogue technologies, have inexorably merged as have the digital technologies and applications now used to gather and produce the news… Used in conjunction with established communication and information technologies (such as broadband access to the Internet and one of its applications, the World Wide Web), these technologies enable single operators to gather, produce and transmit an electronic news product globally in a matter of minutes (1999, p. 2).

They encouraged those of us who were teaching media production and enjoying the digital technology tsunami taking place in the 1990s by saying, “There is no room for technophobia in the future of electronic newsgathering and journalists will be expected to interact with their audiences in ways they have not been required to previously” (Tickle & Keshvani, 1999). We have taken their advice. As McNeal and van‘t Hooft (2006) note, much has been written about the potential for mobile technologies for education. We have witnessed the blurring of professional, prosumer, and consumer production that was predicted by Toffler (1980) as the rise of a prosumer market brought about by the commercialization of technology. The result was a shift in the 1990s with the democratization of low cost equipment and software. That shift continues to manifest in various personal mobile devices.

Mobile device advantages include relatively low cost, ease-of-use, networked communication, interactivity, and connectivity. They allow users to go beyond space/time limitations of traditional bricks-and-mortar teaching and learning.

Individuals are able to collaborate, create new knowledge, and share information through text, images, footage, and sound immediately with one another or the Internet, synchronously or asynchronously. Using mobile phones as cameras to shoot live events and interviews takes advantage of this trend, and acceptance by an audience for viewing such sound and images in lieu of more traditionally produced media only normalizes such use. Judging by number of hits YouTube videos and web links are getting that deal with using smartphones for filming, a global public is becoming accustomed to the idea of using and consuming content created this way. Hall (2013) notes, “Despite groans from professional and the present (although evaporating) stigma of shooting ‘film’ with a mobile device, it’s happening. It is rapidly re-constructing markets, industries, business models and relationships around the world.” Cameron (2007) adds, “The mobile telephone has become a significant instrument in the development of this journalistic form” (p. 1). The International Conference on Communication, Media, Technology and Design notes advantages of connecting course content in a digitized professional work environment to a “connectivist” approach (Boers, Bilgiç, Rinsdorf, & Vaagan, 2012).

Using hands-on learning and real-world resources in the classroom can make education more meaningful and relevant to learners. Incorporating emerging technology, mobile phones, and social media into learning and professional training responds to this need. The disruptive innovation (DI) theory developed by Christensen and Bower (1995) has been one of the most influential concepts regarding technology and markets in recent years. Christensen (1997) states that disruptive technologies have features that customers value. Products based on disruptive technologies are typically cheaper, simpler, smaller, and, frequently, more convenient to use (p. xv). Berenger and Taha (2012) remind us how other disruptive technologies have had profound effects on knowledge, geographical boundaries, social interaction, and delivery of information. In his book The Mobile Wave, Michael Saylor (2012) describes mobile media as “disruptive” and revolutionary, fundamentally changing our lives and having the ability to alter education. He calls this transition to mobile devices, “the fifth wave of computing — the first was the main frame, the second was the mini-computer, the third was the personal computer (PC), and the fourth was the Internet-linked computer (Miller & Chapin, 2012).

The following questions were explored: (1) Can a high quality, election news program be produced despite limited resources using mobile phones, traditional media and social media to create a seamless production? (2) Can the program be successfully delivered in real time to a diverse audience of university students, faculty, and the larger western Connecticut region? (3) How well will students of various interdisciplinary majors work together under the stress of a high stakes project? (4) How will the course participants adapt to unforeseen events (the first year, Hurricane Irene barreled through the region, taking out scheduled and necessary dress rehearsal). (5) Can student civic understanding and engagement be increased through such a course?

Participants

Thirty-one students, 22 males and nine females, were registered in COM 298 Faculty Developed Course: Broadcast News and Politics, all from the School of Arts and Sciences. Students ranged from freshmen (1), sophomores (7), juniors (10), and seniors (13). Student majors in the course were media arts, 22; political science, 4; communication, 2; English, 1; professional writing, 1; exploratory studies, 1. An Informational Technology student volunteered to participate on election night. Two additional students from theater arts (School of Visual and Performing Arts) participated without receiving academic credit on set building. Twenty-seven students from COM 270 Fundamentals of Radio Broadcasting, and 15 students from MKT 301 Principles of Marketing (School of Business) assisted with promotion. Twenty-three student senators from the Student Government Association assisted with a “watch party” on campus (two Senators proposed the watch party, 21 approved the motion). Two hundred fifty attendees were estimated to be at the campus-held watch party during the live broadcast. Faculty from Communication and Media Arts, Political Science, Business, and Justice & Law Administration volunteered to anchor and work with students, and from Theater to design the news set built from theater department wood scraps, borrowed classroom stools, and purchased materials.

Procedure

COM 298 Faculty Developed Course: Broadcast News and Politics was created to provide local, state, and national election coverage to an underserved area designed to give a local and regional perspective. The undergraduate course objectives incorporated pedagogy, media production, design, communication, social science, news, computing, basic civics, and technology. The inner lens focused on accurate and compelling storytelling, breaking news, ethics and adaptability all within the context of television production and public service.

The course was designed to produce a live four-hour news and election coverage over Charter Communications “Community Vision” cable access television channel 21, while simulcasting the program over the Western Connecticut State University’s college radio station, WXCI-FM (91.7) and sending a live video web stream on WCSU’s webpage (www.wcsu.edu/live). Preparation for the live broadcast began months in advance, building on the school’s historical first election broadcast in 2011. Students and faculty from over 10 different academic departments and offices were involved including Communication and Media Arts, Social Sciences/Political Science, Professional Writing/Journalism, Informational Technology, Theater, Business Administration, Marketing, Justice and Law Administration, Graphic Arts and English.

In addition to participating in lectures and discussions during the five-hour class, students in COM 298 were required to research, write, record, and edit stories (news packages) beyond class time. By week four, the class was focused into two main groups: those who worked in the field, and those who worked in the studio. Everyone was assigned a position, including faculty who worked on the project: producers, directors, live room techs, audio, camera, anchors, reporters, etc.

The goals of course were to:

• Produce live election coverage programming, using various production and postproduction skills: field reporting, TV studio news production, editing, virtual environments, graphics and set design/creation.

• Teach current news production theory and practice.

• Incorporate ethical practice and professional standards.

• Provide for a strong course meta-structure, with clear task goals, with both “soft” and “hard” due dates for specific tasks.

• Provide rewards for tasks done early and/or very well.

• Provide flexibility and expect personal responsibility within individual and 2-3 threemember group tasks.

• Teach basic concepts in civics and government and relevant current political news.

• Investigate various emerging technologies as an educational tool.

• Provide an interactive learning experience.

• Provide a form of live, inexpensive video recording on location field reporting.

• Provide a way to inexpensively transmit field reporting back to a TV studio.

• Provide a way to disseminate live election coverage to both a large, established audience and a new audience.

• Include various relevant academic departments, students, faculty and university staff.

• Give students the opportunity to work with local and state government leaders, politicians, and media industry professionals.

• Provide a valuable community service by offering live, locally situated, regionally focused election coverage.

• Provide an interactive news program.

Course assessment for reaching these goals included the actual live broadcast (and recorded for review), attendance at the live “watch party,” comparison of test scores over the semester, student evaluations and unsolicited feedback from viewers. Reaching these goals required facing significant hurdles.

On November 6, 2012, live election coverage was produced and delivered from 8 p.m.- midnight. In Connecticut commercial television stations are in Hartford (WFSB, WTIC), New Britain (WVIT), New Haven (WEDY, WTNH), Norwalk (News12), and Norwich (WEDN), but there are no dedicated commercial television stations that focus primarily on local needs of western Connecticut. The course and production goal was to address that need by covering important events in American history, including a presidential election and local and state elections and issues. The broadcast was simultaneously aired live through cable television, FM radio and video steamed via webcast. According to Greg Van Antwerp, Community Access Supervisor at Charter Communications, the program could reach a potential audience of over 60,000 TV households (personal communication, October 4, 2012).

Use of Smartphones. Unlike many academic disciplines, television production is traditionally dependent on having expensive technology and equipment. Transmitters needed to broadcast signals are costly. One way around this is for colleges and universities to be affiliated with, or re-transmit, public broadcast station (PBS) TV signals. Another way is for a school to have its own low-power television station and transmitter (LPTV). Having neither of these options, we were faced with other limitations: no campus TV studio from which to produce or disseminate the program, no remote and field equipment, production vans, or satellites to report from various locations and very limited funds for a news set and desk. Here’s where mobile phones factored in. And determination.

Taking advantage of new technology, one of the more intriguing facets of the live program was the use of Smartphones for live, video field reports from students strategically placed in various towns to cover political races, polling results, analysis and interviews. In the past, extremely costly news production trucks with microwave satellite technology and receiving broadcast towers were needed for such live reporting and news. We were interested in breaking tradition (instead of the bank) by using the phones mounted on tripods as field cameras. We added adapted audio gear and sent out teams of two consisting of a reporter and a camera/audio person. Students reported live from Hartford, Torrington, Stamford, New Haven, Waterbury and Danbury, from various Republican and Democratic Party headquarters in Connecticut.

Program Details. Despite some on-going, sideline nay saying, through months of meetings and managing state, institutional and bureaucratic hurdles, a negotiation was finally reached for collaboration with a neighboring cable company, Charter Communications in Newtown, CT, just days short the fall semester start. After 18 months of planning and with 30 students hanging in the balance, it was a bit of a cliffhanger. Persistence and support from the University and Charter became crucial. Charter allowed us to use their public access TV studio.

For months before the live program, field crews worked on gathering research, interviews and images related to various news stories or “news packages,” while the studio crew also worked on news packages, graphics, the news set and virtual environments to be shown on election night such as the green-screened virtual set and superimposed polling graphics. As election night neared, studio rehearsals were needed to obtain program flow and technical operations worked out. A major and exciting part of the live component was the creation of a “live” room in which several linked switchers and routers brought in six different feeds from the various field crews positioned around the state. A team of four students worked the room; two IT personnel were on hand to assist in case any technical issues came up. The Charter staff was also on hand but did not have to intercede at any point. They watched the show from another room.

In the TV studio, two moderating anchors discussed various topics and issues throughout the evening. Throughout the live four-hour broadcast, eight rotating anchors were brought in, appearing two at a time, for a total of four anchors at any given time (two moderators, two guests). Care was given to feature faculty and student anchors who would bring diverse perspectives to the table.

News Packages and Topics Discussed. “News packages” are prerecorded stories on relevant issues. Twelve prerecorded news packages provided visual and rhetorical context to issues, allowing anchors and field reporters to comment on, and react to, how those topics were covered. The four hours of live coverage 8 a.m. - midnight. In addition to following various local, state, and national political races, the following topics were discussed:

• Hurricane Sandy

• Youth Vote

• Electoral College

• Education

• Energy: (Regional) Connecticut Gas Prices

• Energy: (National/Global) Climate Change

• Supreme Court and Implications of the election results

• The Fiscal Cliff

• Campaign Finance Reform

• Health Care Policy and Reform

• Women’s Health

• Role of Women in this election, media portrayals, voting

• Decline of the Middle Class

• Income Gap

• What You’re Not Reading About: Immigration

• Jobs, Unemployment

• The Recession

• Banking Reform

• Mortgages

• Taxes

• The Economy and candidate comparisons

• Global Comparison: US vs. Other nations (education, health, employment, etc.)

• Voter Fraud vs. Voter Suppression

• Super PACs

Since there were no breaks in the live coverage, in addition to assisting anchor commentary, disseminating important information and engaging the audience, news packages were used to cover switching studio anchors. Four of the eight anchors were seen at any given time, seated at the news desk in the studio. Anchors were chosen from Communication and Media Arts, Social Sciences/Political Science, Justice and Law Administration, and Business Administration. Six were faculty, two were students. The two moderating anchors brought experience and professionalism to the program from having appeared (and continue to appear) as experts on various commercial television networks (CNN, Fox News, MSNBC, etc.).

Intermittently throughout the night, a second area in the television studio featured a political science student who gave polling updates and covered political races while appearing in front of the virtual set of superimposed polling numbers from various races. Next door in the control room, a student updated those numbers using Live Text, software that worked with switchers in the control room. The control room was filled with various producers, directors, audio, graphics and technical personnel most of the time, with several talking at once, shouting out orders for shots, audio cues, remote feed inserts and the latest polling data. Producers guided the live show content. The two moderating anchors were constantly receiving cues and information about where to go next from the director in their respective ear pieces, or “interruptive feedback” (IFB). The field crews were communicating with the “live room” crew who patched in their respective feeds when the show would go live to them. The three rooms at Charter—control room, live room and studio-- resembled a very active hive, live with action, dialogue, electronics and social media.

The anchor desk and set were designed by an Emmy Award-winning scenic designer Professor Liz Popiel, Art Director on weekends for Good Morning America (WABC-TV- NYC). Two theater students built the set and desk, using existing and new materials.

Additionally, a “Watch Party” organized with support from Student Government was set up in the campus Westside Ballroom to allow students and members of the community to watch the live broadcast on large wall mounted monitors. Students were able to interact with the show through Twitter and on-camera interviews with on-site student reporters. More than 250 people attended, according to faculty member and radio station advisor Tom Zarecki. Updates were periodically shared on the mood of the room, energy and interest in civic engagement. Refreshments were provided to help fuel the attendees over four hours. The room would erupt when certain races were called. A partial list of attendee names and emails was gathered as a source for feedback and future election show updates and promotion.

The technology mix: Collaborating with Charter Communication was successful, mutually beneficial and rewarding. Last year, Charter competed against major networks and submitted our 2011 election coverage in the Education Category for the coveted Beacon Award from the Association of Cable Communicators. Charter was a national finalist for that award. Our collaboration also offered a significant challenge, however; this one, technical in nature. To accomplish the goal of providing the live field reports was not possible without adding two additional video switchers from WCSU, which allowed for creating virtual sets and incoming web-based signals, mixed with traditional studio sources (cameras, graphics generators, audio, etc.) to form a complete synchronized signal for broadcast, cablecast and webcast simultaneously. There was still one problem: how to record those field reports Smartphones provided the answer, along with some additional technical adaptations provided by our IT professionals.

Our technology “cocktail” grew. The use of virtual news sets was incorporated along with actual physical sets and a news anchor desk. Class file sharing was used via a dedicated server for uploading and downloading audio, video, and graphic files for prerecorded segments. Text messaging, “the currency of modern conversation,” (Sutter, 2012, paragraph 3) was used throughout the semester to give students class and news story updates, as well as for communication between Charter’s control room crew and students in various locations in the field. A RSS (Rich Site Summary) feed, which allowed for regularly changing web information to be received, was set up to aggregate news and gather headlines from Reddit. That was fed into Live Text and used to update the crawling feed at the lower third of TV screens during the live program.

A Face Book page was created for the program along with a Twitter account to assist with promoting the show and keeping a running record of progress from various stages of production and during the live show. Promotional information on the show before it aired was also sent to Instagram. A phone number was given to the audience to call into the show while it was in progress to talk with anchors. A traditional landline at Charter was input to the audio board. We also set it up in case any of the smartphones used as field cameras went down. If this happened, a reporter could call in, and a still picture of them (taken ahead of time with a smartphone) was on file with the switcher, to accompany their live voice call-in. At one point, a professor from the School of Business called in and wanted to talk “live” to the anchors about an issue. Students in the control room immediately brainstormed, then flew into action, obtained his picture from Facebook, downloaded it, imported it into the video switcher’s computer, brought in up through a split-screen image with one of the anchors and brought in his live landline phone call for voice-over, patched into the audio mixer. This was all done within minutes, behind the scenes, without any discernible break in live program flow as the producer and director were communicating with studio anchors via ear pieces, and anchors spoke to the audience and with one another. Being able to listen to directions from one person and hold a conversation with someone else at the same time is a skill in itself. The anchors did it well. It was pre-show “what ifs” preparation that helped problem-solve this particular challenge. The audience had no idea of the various levels of controlled chaos and communication that was taking place, during this and throughout the entire show. And they should not, of course.

Limitations

Personnel requirements: Support from University IT in the form of personnel and equipment was essential. Additional support from the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning, various faculty, departments and university offices such as the Publications and Design, University Relations and Administrative Services was vital. Sustaining these working, supportive relationships is critical for the success of such a large endeavor, especially one with a public face. Maintaining faculty with passion and expertise to manage and participate in such an operation is essential. Interdisciplinary cooperation and teamwork are vital.

Curriculum: A course proposal has since been approved at the departmental and institutional levels. This will facilitate curriculum stability, better consistency in election coverage, improved enrollment, and audience building.

Facilities: The facilities used were ten miles outside of campus in Newtown, CT, with limited hours of access. Future collaboration with regional cable and media companies should continue. However, a dedicated campus television facility is very strongly recommended. Students need to be able use all of the equipment, not just some equipment, to learn and use. Students need to have more and easier access to the control room, audio booth, live room and studio. Having an adequately equipped, fully functional campus television facility will allow such learning.

Use of Equipment: Additional improvements include a computer generated map of election races included for the virtual set. Limitations existed with getting multiple graphics simultaneously on the screen such as polling results, Twitter feeds, virtual sets and names of anchors. This is something for the instructor and students to figure out—a good challenge for the next show. Planning for such an improvement should start immediately and may require assistance from the department and/or information technology (IT) professional on campus.

Better feedback planning and means: Better means are recommended for gathering student input at future watch parties. This year, it was done as a last minute thought. Additionally, a survey sent to the university community within 48 hours after the election is suggested. A draft of that survey, to be offered through Survey Monkey, is included in Appendix C, Election Connection Survey.

Future research: For research purposes, preparation for obtaining additional, relevant participant information is suggested. Designing the course with the inclusion of a pre-/post-test would allow for measuring student performance in certain areas such as current affairs knowledge, civic understanding, interviewing skills, trouble-shooting, and news production procedures. Such a study requires IRB approval.

Four tests were given over the semester, ending with a cumulative final exam. Test scores for the class improved from the first test to the final exam by an average of 8.61 points.

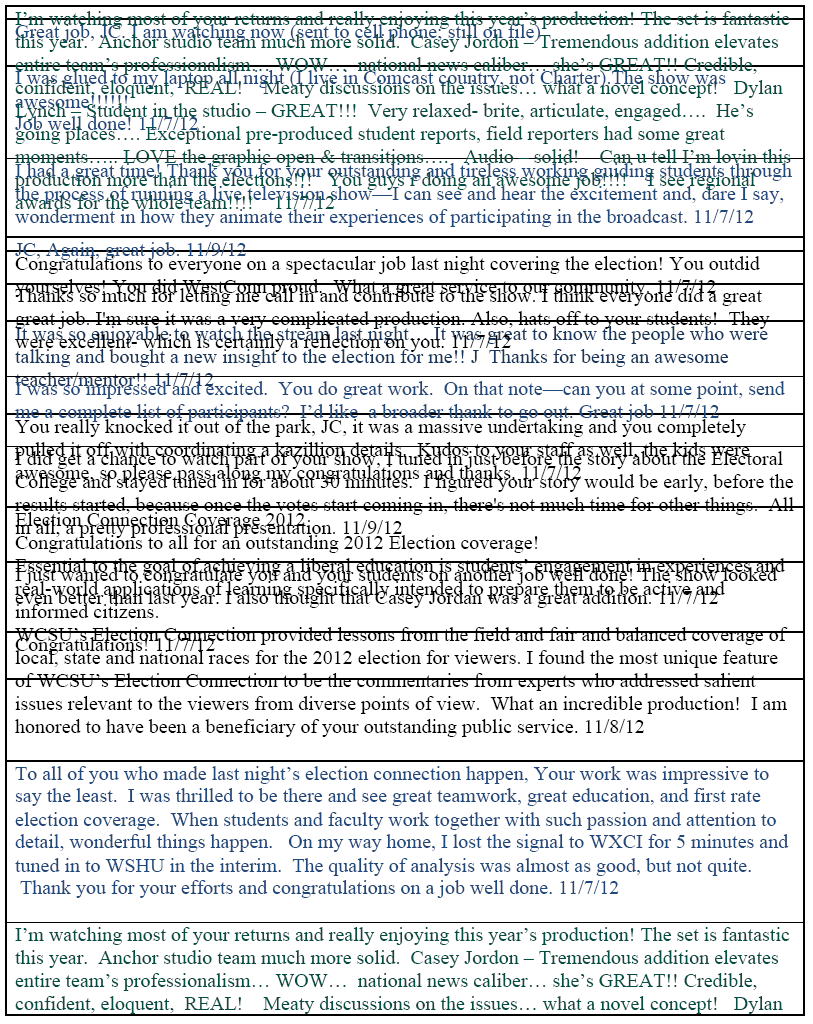

Feedback sent to the producer’s WCSU email was positive. All of the email responses are attached in a table in Appendix A: Unsolicited Email and Text Feedback. All original emails have been saved for examination. Names of senders were removed and may be requested upon receiving the individual’s permission to share it.

Watch party

Approximately 250 students were estimated to have shown up at the Westside Ballroom according to Communication Professor Tom Zarecki and a student election reporter who were in the Ballroom (email communication, December 20, 2012). Students stayed throughout the broadcast and could be seen when the program went “live” the Ballroom, to the reporting student and professor. Names, year (freshman, sophomore, etc.), and major were gathered from students who entered the Ballroom during the first hour and submitted to the Communication and Media Arts Department and the Office of the Provost.

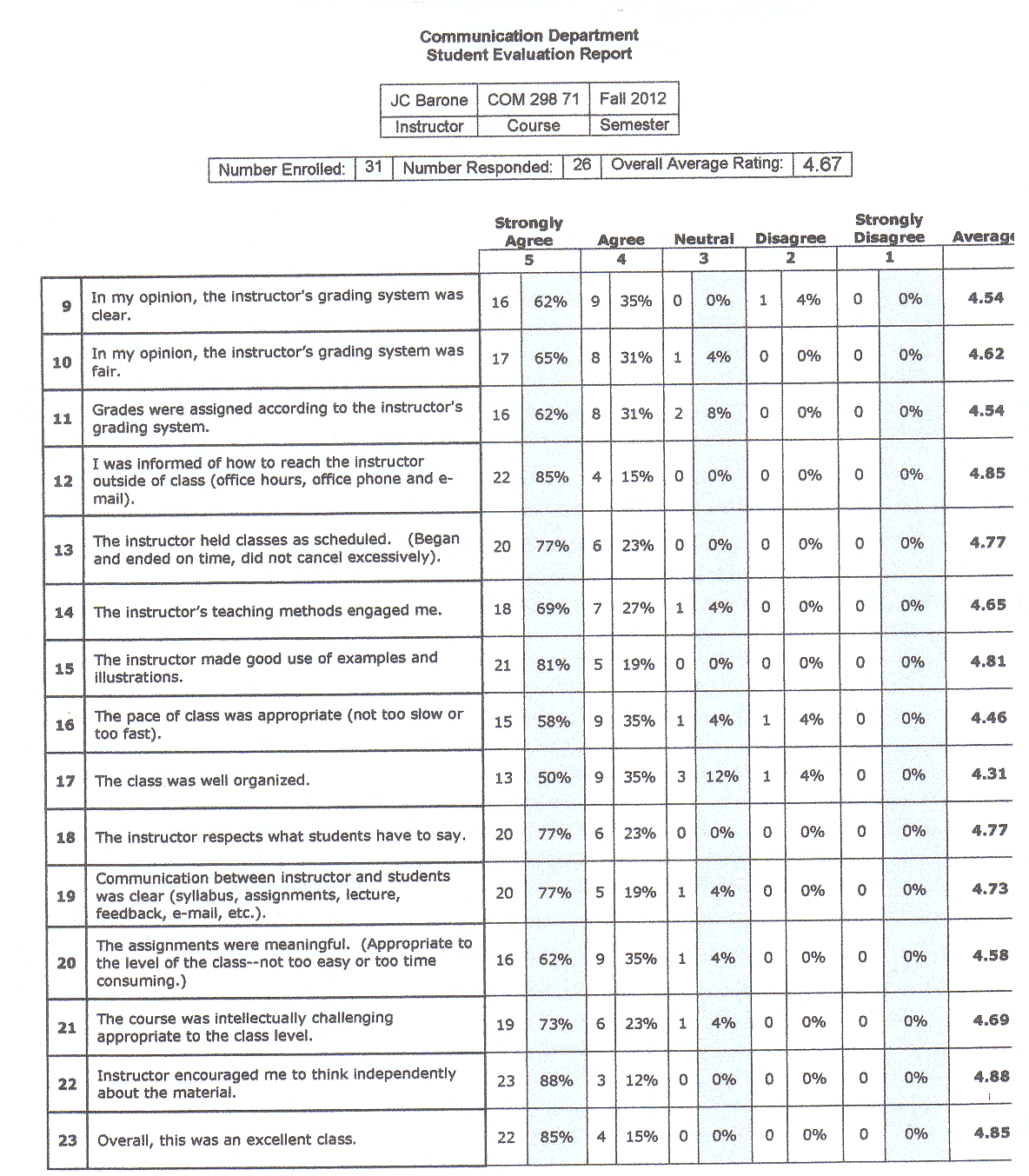

Data was collected at the end of the course through course Student Opinion Surveys and showed an average rating of 4.67 out of 5.00 for 15 items that dealt with evaluating the course (Appendix B). Rating on individual items ranged from 4.31 (“The class was well organized”) to 4.88 (“Instructor encouraged me to think independently about the material”). A general item, “Overall, this was an excellent class,” showed an average of 4.85.

Additionally, shortly after the election an invitation to present the course and broadcast was sent to industry professionals and educators:

Sent: Tuesday, November 20, 2012 1:23 PM

Subject: BEA 2013 Panel Submission

Congratulations! Your panel submission to the Broadcast Education Association division of Interactive Media and Emerging Technologies has been accepted for the BEA 2013 National Convention.

The Broadcast Education Association is the professional association for professors, industry professionals, and students who are interested in teaching and research related to electronic media and multimedia enterprises.

Lastly, the live program, “Election Connection 2012” was submitted to professional media competitions. It won two awards, a prestigious Telly Award, and the International Academy of Visual Arts’ Communicator Award of Distinction.

The following areas were explored: (1) Can a high quality, election news program be produced despite limited resources using mobile phones, traditional media and social media into a seamless production? (2) Can the program be successfully delivered in real time to a diverse audience of university students, faculty and the larger western Connecticut region? (3) How well will students of various interdisciplinary majors work together under the stress of a high stakes project? (4) How will course participants adapt to unforeseen events? (5) Will student civic understanding and engagement be increased?

Success of the course was assessed from four sources: (1) test scores over the semester, (2) unsolicited email feedback during and after the show, (3) attendance at the campus “watch party,” and (4) student opinion surveys from the course.

The live broadcast was carried out for four hours as planned. Original graphics were professionally crafted. The news desk and set belied its humble origins of discarded wood from the Theater Department, the rotating faculty and student anchors delivered poignant commentary and analysis live, uninterrupted from 8 p.m. until midnight EST. The student positioned in front of the studio polling data virtual set delivered polling numbers and commentary, the six remote field teams located throughout the State delivered informative political party headquarters information, “mood of the rooms,” interviews, and analysis. A live call-in was included in the show. Tweets and Internet research and polling data were continually updated on the lowerthirds graphics at the bottom of the screen. Prerecorded news packages on topical issues were interspersed throughout the program. There were no breaks, commercial or otherwise. No loss of transmission occurred during the broadcast. A DVD of the entire program is at WCSU’s Haas library and online at: https://vimeo.com/67361002 Election Connection 2012.

The live program, “Election Connection” won two prestigious awards in professional competitions. Feedback indicates audience members included students, faculty and members of the community. The campus watch party had approximately 250 students attend throughout the evening. A 15 item student opinion survey yielded positive results with an average course rating of 4.67 out of 5.0, and specifically on the item , “Overall, this was an excellent class,” 4.85.

Moving beyond digital distraction, mobile devices are being used to engage, teach, and learn. The EDUCAUSE 2012 Horizon Report cites flexibility, mobility, collaboration, cloud and web-based learning and more emphasis on “challenge based and active learning” as emerging technologies areas to enter mainstream use over the next five years (Johnson, Adams, & Cummins, 2012). Training Tomorrow's Television Journalists: In the Trenches with Media Convergence (Tanner & Smith, 2007) studied the practices of news workers in the top 50 television media markets and below, markets in which journalism students usually obtain their first jobs. Data revealed nearly 70 % of respondents personally performed convergent tasks (p. 211).

The media landscape is changing due to emerging media: mobile communication, social media and networking, virtual environments, and easily purchased cameras and audio gear. Jobs lost in print media are being picked up by electronic media, “the first time we’ve seen this kind of substitution,” states Pew Research Center’s Project for excellence in Journalism in their annual report, the State of the News Media (2012, para. 12). The International Conference on Communication, Media, Technology, and Design state,

The consequences of convergence for journalism are obvious: distribution channels like radio, television, online and print are no longer separated. Established workflows, which focus only on one channel, are no longer suitable. They have to be replaced by new forms of cross-media production which consider the multi-channel-perspective from the beginning. Journalists and media marketers have to cope with some challenging tasks on their way to convergent products and production workflows (Boers, Bilgiç, Rinsdorf, & Vaagan, 2012, p. 229)

Smartphones and Internet-based laptops made this project and live, mass audience program possible. We tapped into the fourth and fifth waves of computing, Internet-linked computers, and mobile devices respectively (Miller & Chapin, 2012), on several levels, from various studio and field production activities, GPS, social media, and the interactive live watch party. Smartphones played a significant role, and no surprise. Not only were they useful, but we love our phones, our “phantom limb” (Sutter, 2012); 68% of us sleep with them at our bedside and three-quarters of Americans feel that constantly connected by technology is helpful (Qualcomm & Time, 2012, http://www.time.com/time/interactive/0,31813,2122187,00.html).

While commercial and non-profits are still figuring out the best way to manage, produce and disseminate local news, the Pew Research Center (2012) found that one of major trends in news media is that “local news remains the vast untapped territory” (para. 20).

The use of emerging technology must be factored into teaching and learning more—or educators will be left in the dust as learners take learning upon themselves. Add to this the fact that today’s undergraduates are working more hours while attending college, an average of 10-15 hours a week fuels this need. Today nearly one in ten full-time, traditional-age undergraduates is employed at least 35 hours per week (AAUP, 2010). Institutions are not always willing to change or able to adapt quickly. In many ways the manner of teaching has not fundamentally changed in over 100 years. We are well into a new paradigm of learning and living brought about by the digital wave. Will there still be a need for brick-and-mortar campuses? Perhaps. There are good reasons to do so. Changes in scale and purpose will likely occur as blended synchronous and asynchronous teaching and more independently based, pedagogically guided learning takes off. With this converged project we jumped on and rode the wave.

[SURVEY PREVIEW MODE] JC Barone, PhD/ Dept. of Communication & Media Arts Election Connection

1. Prior to the election on November 6, 2012, did you hear or see anything about

WCSU’s live election coverage, Election Connection?

• Yes

• No

2. If yes, do you recall how? (Check all that apply)

• Posters

• Face Book

• Twitter

• Lawn signs

• Radio

• TV

• Read about it

• Word of mouth My professor Other (please specify) ______________

3. Did you watch or listen to WCSU’s live coverage on election night?

• Yes

• No

4. If so, how did you experience Election Connection? (Check all that apply)

• cable

• TV

• radio

• Internet

• mobile phone

5. How would you describe WCSU’s live election night broadcast? (Check all that

apply)

• Balanced

• Unbalanced

• Variety of viewpoints & perspectives aired

• Well-crafted news stories and interviews

• Professional graphics

• Good reporting

• Good analyses

• Timely and reliable polling results

• Other (please specify) _________________

6. What did you like the most from watching or listening to Election Connection?

(Check all that apply)

• Live reports from various locations

• Important issues covered

• Studio anchors and discussions

• Twitter comments and updates on the screen

• Up-to-the-minute polling results for local races

• Up-to-the-minute polling results for Connecticut state races

• Up-to-the-minute polling results for the presidential race

• Professional graphics used

• Quality and professionalism of student reporters and crew

• Connecting to the live WCSU Westside Ballroom viewing party

• Other (please specify) ______________________________

7. How long did you watch or listen to Election Connection?

• Off and on throughout the four-hour broadcast

• Less than 30 minutes

• About an hour

• About 2 hours

• About 3 hours

• The entire show

• Did not watch or listen to the program

8. How likely are you to watch or listen to WCSU’s Election Connection live

coverage in the future?

• willing to check it out

• looking forward to seeing it next year

• won’t watch or listen to it

9. How do you usually follow election coverage and results? (Check all that

apply)

• Newspaper

• Radio

• TV

• Internet

• Blogs

• Mobile phone

• From other people

• I don't watch or listen to elections

• Other (please specify) _______________

10. Is there anything else you’d like to share about WCSU's live election

coverage? ________________________________________________

Copyright © 2024 Global Media Journal, All Rights Reserved